At a Crossroads of Identities

From an early age, I was taught to be proud of my Haitian identity.

In elementary school, I was taught the history of Black slavery and the heroes of Haitian independence; Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Alexandre Pétion, Capois Lamort who had defeated Napoleon’s army and gave birth to the first independent Black Republic in 1804. This victory belonged not only to the Haitian people, but to all black people around the world who suffered slavery and colonialism linked to the ideology of white supremacy. Even today, this story is still taught in African countries and inspires young generations. In a world where the history of Black cultures and peoples is misunderstood, erased and considered inferior to white Western cultures, it is essential for a Black person to know their history so as not to be locked into the vision of their identity as shaped by Western culture and embodied by the white man. This is necessary for self-construction based on one’s true heritage.

However, the teaching of Haitian exploits was not enough for me to know myself and fully identify with my community. I didn’t just have one identity. My sexual attractions gave me a second identity that contradicted the first. As a teenager (in the late 1990s and early 2000s), for Haitians, homosexuality did not exist. It was a white man’s thing. And this mentality was widespread in all Black communities. How could I be proud to belong to a community that doesn’t allow me to be myself? I don’t remember seeing images of Black people from the LGBTQ+ community. It’s hard to build yourself without role models and a history to reference. Like many other people, my first images of the gay community were those of white men, since western countries were the first to talk about rights for LGBTQ+ people. Not wanting to live in shame for who I was, I sought out the history of this second identity that was awakening in me in the history of these other people who, historically, had been hostile to what my cultural origins represented.

Ironically, my journey in the LGBTQ+ community led me to reconnect with my Haitian identity. It allowed me to discover more about the richness and diversity of Black cultures. I understood how the notion of pride I had developed in my Haitian identity, while revolutionary, was influenced by similar criteria used by others to reject Black Haitian culture. Haitian history was valued by celebrating the achievements of the indigenous victory by force of arms, but denigrating the culture that had made it possible. For example, they celebrated the achievement of the enslaved Black people who had won the Battle of Vertières, which would lead to Haiti’s independence, but forgot that they had done so because they had preserved an ancestral spirituality, voodoo, and were united around a new language, Creole. I was taught to take pride in the French language while denigrating Creole and to adopt Christianity at the expense of voodoo. In order to achieve pride by Western standards, our heritage had to remain partly in the shadows. However, in this part of history that was kept secret, there were other roots that connected me to myself.

Jackson from the TV series Pose

By digging into the marginal areas of history, I found evidence that what I was told was incompatible with my Haitian identity, was not. By meeting Erzulie Freda, the spirit of love and desire, the embodiment of female strength in voodoo and patron saint of gay and lesbian people, I was able to lift the veil on the place of LGBT people in the very roots of Haitian culture.

By joining the black LGBTQ+ community, I was able to meet Black people of diverse backgrounds who had also grown up feeling that they were the only ones in their communities to be attracted to people of the same gender. In 2009, I walked in the Pride Parade for the first time with the group Arc-en-ciel d’Afrique. It was important to show others that we exist to foster this better self-construction. For our stories to be more than just stereotypes, the individuals who make up our communities must be able to display their complexity and express their various facets. Arc-en-ciel d’Afrique took part in 9 editions of the Montreal Pride before closing its doors. Members from several African and Caribbean countries came to walk with the flag of their respective countries, in an effort to reconcile identities that some claimed were incompatible.

Times change. What was irreconcilable in my childhood and adolescence is no longer so. In anti-racist struggles, Black LGBTQ+ people are increasingly speaking out and working for the recognition of intersectionality. The fight isn’t over, but young Black people are nowadays evolving with more and more images of queer people in Black communities. A number of public figures are now on the public eye such as singer Lil Nas X, director Lee Daniels, actresses Laverne Cox and Raven-Symoné, to name but a few. Black people from the LGBTQ+ community are also starting to occupy the small screen with television series such as Pose, RuPaul’s Drag Race, Noah’s Arc, Dear White People and many others. These models are revolutionizing the way these communities are seen, casting new light on the complexity of their past and their present day realities. Even in Haiti, the issue of the LGBTQ+ community is increasingly addressed in the media. In July 2020, the Haitian government proposed a decree prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation. Thousands of people took to the streets to demonstrate their disagreement, fuelled by their evangelical Christian faith. However, I cannot help but see this new amendment as a step forward for the rights of LGBTQ+ people in Haiti. What was unthinkable when I was 20 years old is becoming possible in 2020. It is obvious that there will be resistance; the privileged classes are not giving up their privileges without opposition either. But making its voice heard and signaling its presence is already a victory. On the other side of the Atlantic, in Africa, the first Pan-African Pride will be celebrated this summer in a virtual way. In all the upheavals we are witnessing around the world, things are moving for the better. More and more marginalized groups are rising up to take their place in the public space.

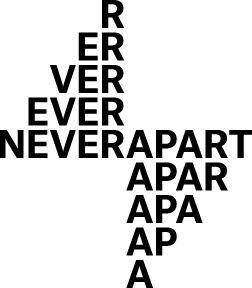

As Montreal’s LGBTQ+ community prepares to celebrate Pride from August 10 to 16, let’s remember that our pride encompasses our belonging to several identity communities at once. Being who we are rarely comes down to a single identity. We are the sum of many different elements. We enrich all of our communities by bringing the pieces that make us up in each of them. Let us remind others that they are not alone, displaying all our differences. By asserting ourselves, we allow others to recognize themselves and in turn to display their particularities. Every struggle for the recognition of rights inspires others to stand up against the injustices they suffer.

This year, our world is experiencing a new situation with the Covid-19 pandemic. Unlike previous years, the Pride festivities will not be able to take place in physical spaces. It is true that coming together with our peers in the same space is at the root of our struggles, since it is also about breaking the isolation that many LGBTQ+ people experience. However, online presence also allows us to strengthen our ties. Even though Pride activities will be virtual this year, they remain all the more meaningful for people who are twice as isolated in the current period.

I invite you to take a look at the Montréal Pride program. An entire section entitled L’heure Afro Fierté centres the realities of Black queer people.

Don’t forget also to follow the First Pan-African Pride online.

About the Author

Laurent Maurice Lafontant is born in Haiti and has immigrated in Quebec in 2001 where he has been living since then. He has graduated in Fine Arts from Concordia University after achieving a double major in Film Studies and French Literature. Laurent has been involved in the LGBTQ+ community since 2008. He is a volunteer for Gris-Montreal an organization that raises awareness against homophobia. Laurent has been a volunteer and an employee at African Rainbow, an organization that worked with Black LGBTQ+ people in Quebec. He directed two short documentaries Be Yourself (2012) and Beyond Images (2014). Both films talk about Black LGBTQ+ people in Montreal. Laurent is now president of Massimadi Foundation, the organization behind Massimadi: an Afro LGBTQ+ Film & Art Festival. Laurent is also a self-published writer who launched his book “La dernière lumière de Terrexil” in spring 2018.

View Comments

No Comments (Hide)