In Spirit: Living Space

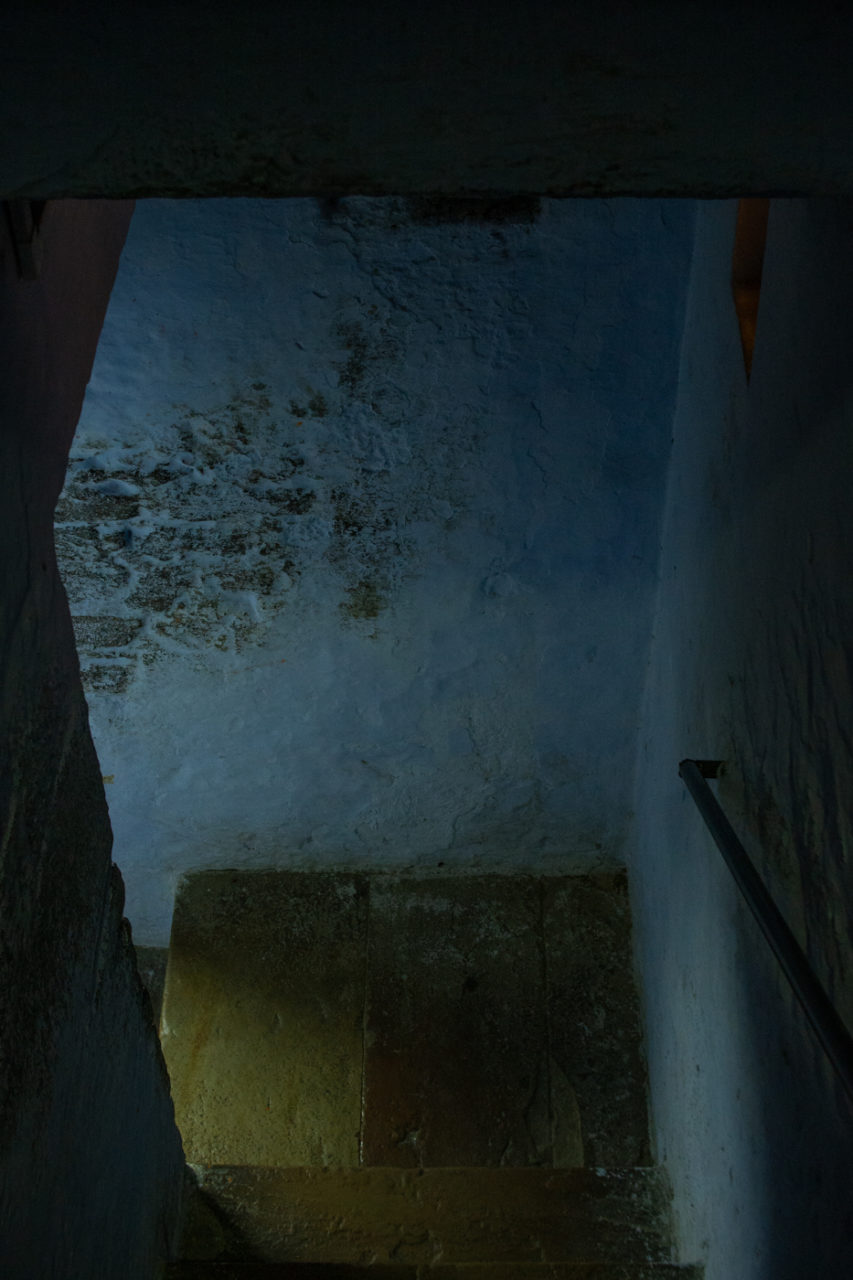

The space of the ground, that of the area, that of the stars. Shadow and light. These elements raise questions that have always been since the dawn of time. Today, if our cycles are regulated by our watches and cell phones, and our knowledge of astronomy from our youngest age, in a remote era was the only observation that allowed men of the great civilization to understand that there were daily, monthly, yearly cycles. The cycle of the sun, moons and seasons was the one that regulated hunting times, planting times, ritual times. The mystery of the universe coming back on itself, the passage of the light of day, to the shadow of the night, are areas filled with secrets that the ancients were able to link to spaces of beliefs, spirituality and teachings.

The house, the den in which we build our intimacy, is a very special space that mimics and defines itself from the world around it. Our living space, changing throughout history and varying from one culture to another, nevertheless has certain identical principles when it refers itself to the traditional principles that underlie its aesthetics.

Do you look at the space in which you live? Do you stop sometimes during the day to observe the movement of the sun and the shadow that inhabit your environment?

This month is space we are going to talk about. For that, I will invite the words of some writers and observers, who have made this path of exploration of this universe that is the place in which we live in. We will see how it underpins the principles of the art of living.

The art of space is something that one finds in a very developed way by the traditional Japanese culture. The author Jun’Ichirô praises the shadow and reveals all the subtlety in the use of Japanese interiors. He explains how certain materials or textures should not be seen in the shadows. In our day – he insists repeatedly in his works – the light brought by the electricity that “lights up” everything is a violence against these interiors and materials that were once only revealed by the flame of a candle or an oil lamp.

When describing one of his favourite restaurants, he shares: “Many customers complained that the candlelight was too dark, they could not do otherwise (but installing electricity), but for those who prefer as before, one can bring candlesticks. As I had come precisely for this pleasure, I had candlesticks put on, and I realized that the beauty of the Japanese lacquer was only fully revealed in this kind of indistinct glow. (…) [lacquers] seem to be born out of necessity from the shadow that surrounds them.”

Jun’Ichirô continues his praise of the shadows, using poetic language to describe the way in which the gold found in a thin line on lacquered materials or more fully on idols (Buddha among others) should never be seen in full light. Gold was chosen for its reflective quality, which does not tarnish, unlike silver, allowing, in a dimmed space, to appreciate all the beauty of the object.

“The aesthetics of Japanese interior is entirely in shades of shadow and darkness or is nothing. When Westerners are surprised at the sobriety of Japanese pieces, made up of walls stripped of the least decorative elements, they are not wrong, of course, but they do not understand the mystery of the chiaroscuro (…) The genius of our ancestors has thus given the world shades of shadows that arise naturally from the intentional filtering of a space made of emptiness, with a grace more subtle than any fresco or decoration. It seems an easy choice and it is not. It is easy to recognize that everything has been thought of, even though it is not obvious at first sight.”

In this culture of subtlety, light, as it dresses space, is thought and observed. It guides the eye but does not give it everything, allowing the eye to learn to see, to learn to appreciate what is hidden. This awareness of space does not use light to “see”, but on the contrary makes it all its poetic form. The light becomes a metaphor for the journey that guides the gaze to teach it to observe, and thereby to bring back the inner state of introspection. This perceptible but not totally revealed space is a praise to this indefinable presence that surpasses us, this presence that we can foresee but that the mind can not describe.

There is the gaze which is satisfied with the external form, and that which really observe at the movement of the world living by its own dynamic, beyond its static external form. The outer form is a bridge towards the most subtle. The look that really looks, is like a touch. In terms of touch, it is Jacques Lusseyran, who praises it. In his biography, he shares the experience that follows his blindness accident at the age of 8 years. He rediscovers the vision through his fingers and learns to truly touch the world around him.

“Our eyes run over the surfaces of things. All they require are a few scattered points, since they can bridge the gap in a flash. They “half see” much more than they see, and they never weigh. They are satisfied with appearances, and for them the world glows and slides by, but lacks substance. All I needed was to leave my hands to their own devices. I had nothing to teach them, and besides, since they began working independently, they seemed to foresee everything. Unlike eyes, they were in earnest, and from whatever direction they approached an object they covered it, tested its resistance, leaned against the mass of it and recorded every irregularity in its surface. They measured it for height and thickness, taking in as many dimensions as possible. But most of all, having learned that they had fingers, they used them in an entirely new way. When I had eyes, my fingers used to be stiff, half dead at the ends of my hands, good only for picking up things. But now each one of them started out on its own. They explored things separately, changed levels and, independently of each other, made themselves heavy or light. Movement of the fingers was terribly important, and had to be uninterrupted because objects do not stand at a given point, fixed there, confined in one form. They are alive, even the stones. What is more they vibrate and tremble. My fingers felt the pulsation distinctly, and if they failed to answer with a pulsation of their own, the fingers immediately became helpless and lost their sense of touch. But when they went toward things, in sympathetic vibration with them, they recognized them right away. Yet there was something still more important than movement, and that was pressure. If I put my hand on the table without pressing it, I knew the table was there, but knew nothing about it. To find out, my fingers had to bear down, and the amazing thing is that the pressure was answered by the table at once. Being blind I thought I should have to go out to meet things, but I found that they came to meet me instead. I have never had to go more than halfway, and the universe became the accomplice of all my wishes. If my fingers pressed the roundness of an apple, each one with a different weight, very soon I could not tell whether it was the apple or my fingers which were heavy. I didn’t even know whether I was touching it or it was touching me. As I became part of the apple, the apple became part of me. And that was how I came to understand the existence of things. As soon as my hands came to life they put me in a world where everything was an exchange of pressures. These pressures gathered together in shapes, and each one of the shapes had meaning.” (Jacques Lysseyran)

Objects that inhabit a space are as important as space itself. The modern object is usually made to be beautiful and entertaining. The traditional object is made to be touched and to reveal the space. The traditional Indian architecture still found in the villages is filled up with the secret knowledge at the heart of its culture. As for the worldly or devotional objects, often visible in some museums of the world or in private collectors’ home, but also still used in some houses, bear a life that inhabited space. The object is alive.

“The work of art allows the sensitive amateur to momentarily forget the daily problems, to relax a little bit the limits of the acting-self (ahamkara), and to savour the beauty that is offered from the moment, it has the power to temporarily increase and make the sattva prevail. (…) This kind of allusion to an intense aesthetic pleasure, even non-dualistic, shows that Abhinavagupta establishes a very intimate link between the non-dual mysticism and the enjoyment of the beautiful” (Roger Marcaurelle).

The one who touches, the one who sees, in the high sense of these terms, is the one who lets himself be penetrated by the world. It’s a double movement. I can only go deep into the world if I really let it invade me. What blocks this process is the will of the individual, the will to control and impose. Let things come to you rather than going to it.

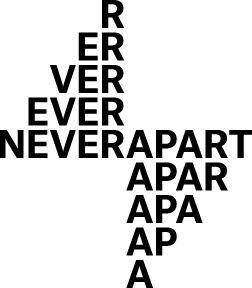

Whether in art, spaces, lessons, conversations, whoever knows this place of observation knows that one must not say everything. In the same way that a room should not be too light up, the spectator must be left to do the rest of the way. This work of traversing the understanding of vision by oneself, such as the eye which seeks light through the shadow, which discerns a space, a landscape, which becomes a poet, is the being returning to an observation without intention. This observation is presence. Art that says too much, be it photography, literature, poetry, painting, film or theatre, is an art that steals, that says nothing. Too much is empty, suggestion is the door to dazzle.

A piece of art or space that offers the beginning of the path pointing toward a direction and the observer that ends it, is a teaching act in itself. The art of living is taught by its light and its shadows, its curves, its textures, its surfaces. Everything is an invitation to observation. When this listening becomes necessary, then only life remains, and contemplation settles on the presence of the moment.

“When the eye of the beholder is free from the subject, from duality, then it sees its own beauty in the object.” (Jean Klein)

View Comments

No Comments (Hide)