Hors scène, avant-scène – A History of La Brique

On an early Saturday morning in September 2013, those of us who called the space known as La Brique home knew it was over. As summer came to a simmer, La Brique was still a jam space and studio by day, but also played host to an increasing amount of parties at night, which concluded with either a sunrise or the Police. In this case, the fire department arrived.

Spaces like La Brique (2005-2013) are significant in their inability to be defined: it was not a traditional jam space or a professional studio, boasting only a small recording studio and a few rooms to set up gear in. It wasn’t quite a place to live in either due to its zoning restructions, but in its early years, there were as many as five residents. Neither was it a venue, yet it hosted hundreds of events in its eight years of operation.

On the fourth floor of a building located at Durocher and Beaubien, pre-La Brique was a sizeable suite occupied by squatter-hoarder-junkies. A crew of recently transplanted Francophone artists hailing from Quebec City started renting it in 2005. According to one of the founders, Xarah Dion, La Brique was started “to reunite all of our activities in an alternative, collective space— to promote avant-garde music and marginal art forms”.

Xarah, along with her friend Asaël Robitaille, were inspired to move to Montreal by local labels of the early 2000s such as Constellation Records and the affiliated DIY space-turned-recording studio Hotel2Tango. Along with their interest in 20th century avant-garde art and music movements, they sought out a space to “share creativity, political beliefs and resources with a larger community”. Xarah and Asaël, along with friends Simon Delage and Jean-Philippe Girard, moved in. Together, they formed Leopard et moi, La Brique’s house band in the early years, a project described on their still existing Bandcamp page as “rock progressive”.

Asaël Robitaille, 2007.

Many DIY spaces in Montreal and elsewhere have seemingly nonsensical, colloquial names. The name “La Brique” sounds benign out of context, but its etymology is telling. Xarah, Simon and eventually Asaël all dropped out of La Fabrique, their hometown art school. Partly a jape to the institution they parted ways from, and a reference to a French expression “attendre avec une brique et un fanal“*, for Simon, it was a place where creative people could work on projects without constraint and “in opposition to a certain scene at that time”. To him, it was “anything we needed at the moment and without limitation: it was a living space, jam space, show space, studio, hang out, communal kitchen… the list goes on.” Xarah recalls a single issue ‘zine they wrote – L’avant-scène – which featured writings from the La Brique collection in addition to other artists and intellectuals such as composer Gabriel Dharmoo and philosopher Alexis Goupil.

* “To wait with a brick and a lantern”

In 2006, Montreal musician Marie Davidson met Xarah and Asaël at a Léopard et moi show at La Sala Rossa. They invited her to a show at “their house”, which seemed like a puzzling proposition at the time. Soon enough, Marie frequented the space daily, playing music and hanging out with the increasing amount of friends of friends of the residents. In the early years, gear was communal: “You had to leave your gear,” Marie insists. The atmosphere was more than ideal for collaboration. Marie and Xarah formed Les Momies de Palerme— another fixture in the experimental landscape of La Brique and beyond. Their immersive performances featured synthesizers, guitar, processed violin and vocals, video projections, props and costumes. Soon after, Pierre Guerrineau met Xarah at their day jobs at a fast food restaurant, a frequent meeting place for members of Léopard et moi. Before local band Essaie Pas were a duo, it was a trio founded in 2008 with Pierre, Marie, and Simon, creating sounds that were more improvised, psychedelic and rock than the synth and drum machine-based songs they’re known for today.

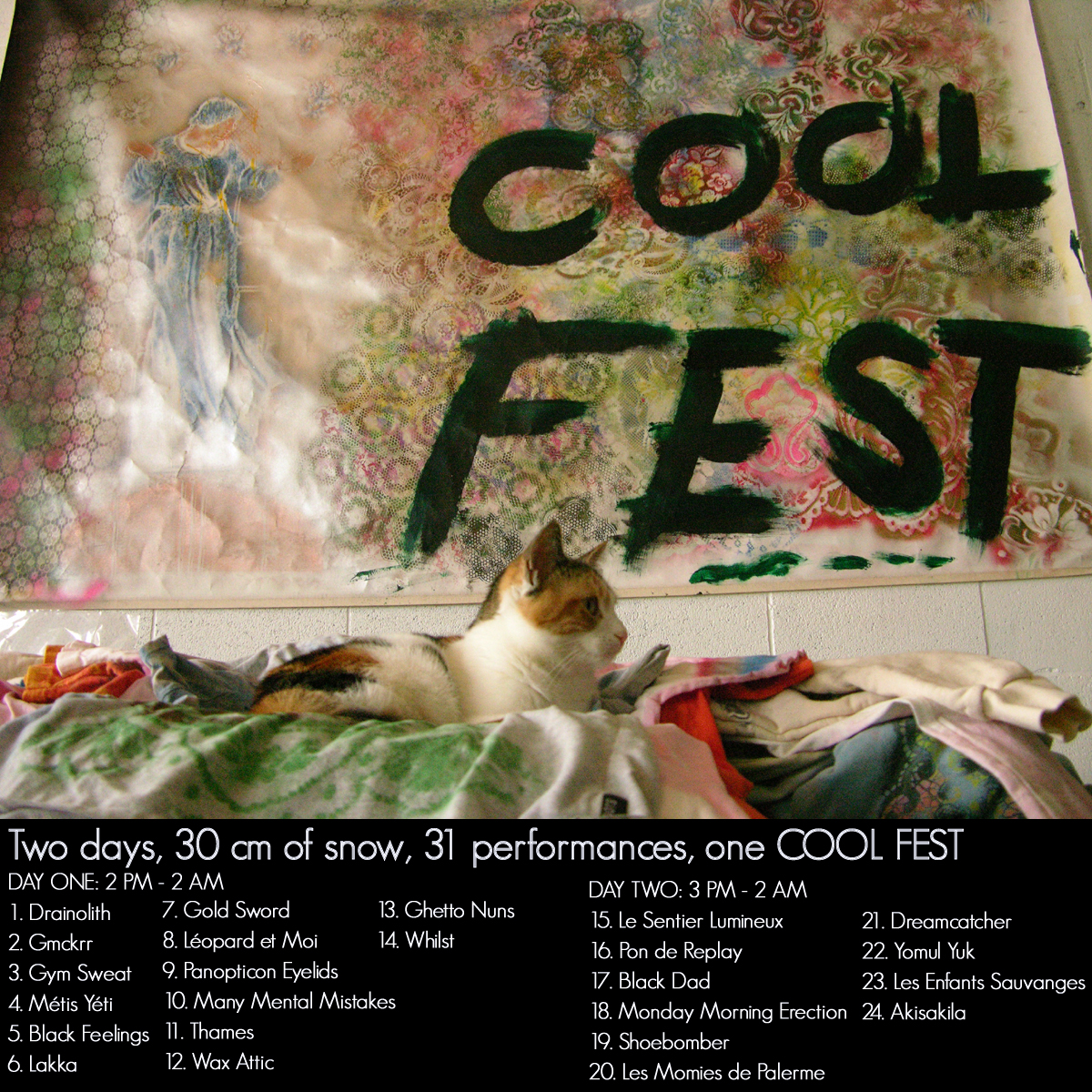

Flyer for Coolfest 7.

“2007 was a moment, like many other times in Montreal’s existence as far as I can tell, when so many fresh people and old masters were playing gigs at so many spaces, I couldn’t always see them all, not least for having plenty of opportunities to play myself. I used to say, one’s fans don’t always come to the gigs anymore, not because they have other gigs to go to, but they all have other gigs to play. And releases to listen to… The weird-music scene at that time saw a lot of people perform well and make it look easy; the fans quickly put together their own groups. The scene was so broad a lot of these people had never met or played together, and I wanted to make that happen.” – Blake Hargreaves, founder of Coolfest

Coolfest was one of the first major events at La Brique, and easily one of the most important throughout its existence. Initiated by a landline-to-landline call from Blake to Xarah at La Brique, the first edition in December 2007 featured 24 performances from local musicians, bringing together like-minded creatives that may have never met otherwise. For many members of the early La Brique community, Coolfest was a highlight, the epitome of what the space was all about. To Simon, it was “overwhelming, chaotic, earnest, out of hand, and the most fun thing.”

Coolfest 7 (named after the year it took place) brought together open-minded Anglos and Francos and manifested itself as something worthy of repetition. Coolfest 8 featured 39 acts in three days, a “merch/dope room”, quadrophonic recording, and two stages. La Brique was an ideal backdrop for the organizers’ ambitious endeavours. The festival is described in its amazingly thorough archive as “a cool festival of music, art and other sensory delights that encourages healthy, heavy partying and intuitive artistic exploration”, which by the accounts of attendees seems spot-on.

Edwin from Tonstartssbandht in the practice space, 2009.

In 2009, the residents of La Brique were forced to move out their mattresses after months of hiding them due to pressures from the city of Outremont, since the space was technically zoned industrial. The collective had to transition away from being a living space and took on new members to help pay the rent. When a similar DIY space called Lab Synthèse closed around the same time, a pre-Arbutus Records Sebastian Cowan set up a recording studio and office space at La Brique. With this change came more interactions with the Anglophone experimental music community. Seb notes that if it wasn’t for La Brique, he may not have started Arbutus, as the move to the new space inspired him to take the shows he was organizing and the bands he was recording to a new level.

2012, the end of the world as we knew it according to the Mayan calendar, was a particularly significant year for La Brique. By Coolfest XII, which featured four concerts held at each solstice and equinox in 2012, it was clear La Brique was a key spot for Anglo-Franco musical collaboration. By then, Pierre would mix and master a lot of bands, most notably Dirty Beaches. Many shows would feature Doldrums, Ramzi, and Nacomi— a healthy mix of North Americans living in Montreal. Teo Zamudio, a member of Nacomi who moved to Montreal from Mexico City in 2012, found La Brique to be an ideal introduction to the city and its music scene. He met the would-be members of Nacomi at La Brique and subsequently founded the now defunct tape label God Athletics.

Paul Trafford, 2013.

By this time, you could pay $80 a month to have a key to the place and come and jam or hang out whenever you wanted to. There were so many friends of friends and people with keys that it was difficult for La Brique’s administrative committee to keep track of who came in and out and who owed them rent. On top of everything, the overall rent had increased by $1,000.00 a month. Caila Thompson-Hannant, who performs as Mozart’s Sister, found this openness – to genres, mediums, scenes – to be overwhelmingly inspiring, despite the fact that it resulted in her gear (and others’) getting stolen at a gig. Although La Brique had a fundraiser for those who were robbed, there was still a feeling of broken trust amongst many members of the community that was hard to shake.

Jean Bourbonnais, who lived in a studio from fall 2012 until La Brique’s demise, ushered in the space’s last phase. He was involved in La Brique as early as 2010, organizing a Montreal Satanism Festival. He was particularly interested in bringing more electronic music to La Brique. Although many acts had been incorporating synthesizers, drum machines, Ableton and the like into their music for years, the techno records played by his new acquaintance Paul Trafford filled a creative void for some of the members of La Brique.

Forbidden Planet in action.

Summer 2013 often featured Forbidden Planet founder Jurg Haller, Paul, and guest DJs and producers playing records or performing live sets until well after the sun had come up. These parties divided the administrative committee: On one hand, they could help pay the rent, on the other, they attracted more and more attention from the fire department and law enforcement due to noise complaints. For many underground dance music enthusiasts, Forbidden Planet parties at La Brique were unlike anything they’d ever experienced in Montreal. Ultimately, it was in the early morning hours of a Forbidden Planet party when a fire alarm was pulled, and La Brique’s reign of suite 402 ended abruptly over the course of the proceeding weeks. Those running the space and its events that summer had been warned that it was not up to code for such tightly packed gatherings, and their landlord was no longer willing to deal with the increasing complications of renting the space to the collective.

The after effects of La Brique’s end were tangible to many. Melodramatic as it may sound, it felt like a death in the family or losing a home in a fire. Nacomi diffused when La Brique disappeared, Teo says he stopped seeing people he would normally see at La Brique as much. Marie and Pierre, who celebrated their marriage at a party at the space weeks earlier, also got kicked out of their apartment around the same time, just as they returned from a tour. Many struggled to find new studio spaces, and if they did, they weren’t nearly as inspiring as La Brique was. It was to many the heart of Montreal when it died.

It is impossible to qualify the value of a space like La Brique in the way that would sound legitimate and neoliberal enough for cultural administratives, but that was largely why it was started in the first place, and that’s certainly its legacy. It was a place to exist outside of the gatekeepers of arts funding with their narrow ideas of what music deserves to be made and heard, outside of venues with huge rental fees, laissez-faire promoters and bookers, outside of places where the noise has to end at a reasonable hour. La Brique has remained a benchmark for what creative communities in Montreal are capable of, and nothing has been quite as avant-scène since its untimely closure.

Special thanks to Xarah Dion, Marie Davidson, Pierre Guerineau, Simon Delage, Blake Hargreaves, Jean Bourbonnais, Caila Thompson-Hannant, and Sebastian Cowan for taking the time to contribute to this feature. Thanks to everyone who made La Brique what it was.

Photo Credits:

Feature Image – Ariane Paradis

Asaël Robitaille – Ariane Paradis

Coolfest 7 – Blake Hargreaves

Edwin – Unknown

Paul Trafford – Christopher Honeywell

Forbidden Planet – Christopher Honeywell

View Comments

No Comments (Hide)