How Anti-Blackness Hides in Quebec

This essay is part of the monthly Collective Culture column. Written by Nicolas André.

I want to offer you, everyone in the crowd, some words of advice. Never pick a side when talking about language in Quebec. It’s a slippery slope, to say the least, and it’s neither a simple nor straight forward topic of discussion. Perhaps another metaphor? Writing about language in Quebec is what walking a tightrope must feel like—it’s hard to find balance. I don’t mean to be callous. But I find this zig-zagging between paradigms to be somewhat exhausting. But now I feel as if I’ve found a milieu.

Back in July, after a day of protesting across downtown Tio’tia:ke/Mooniyang, also known as Montreal, I checked my phone to see that someone had sent me an op-ed published in Le Devoir, one of Quebec’s leading French publications. The title instantly caught my attention, “Se rat kay kap manje kay”, which is a Haitian proverb: “It’s the house rat that eats the house,” roughly meaning, ‘The culprit is found around us or near us’.

There was a lot of upheaval going on in Montreal’s Haitian community at the time: asylum seekers working as orderlies weren’t being guaranteed fair wages or permanent status; Montreal North, a borough with a large Haitian community, had the highest Covid-cases out of any other borough in the entire country; and the U.S.-Canada borders were still closed off from non-essential travelers, including asylum seekers.

I understood that “Se rat kay kap manje kay” had nothing to say about any of that. Rather, the piece insisted upon a long-lasting linguistic kinship between Franco-Quebecers and Haitians—the two ‘French nations’ of the Americas—and displayed ambivalence that Haitians were conforming too heavily to the ‘globalization’ of African American culture.

In moments like these I’m reminded of the time my Mammie—that’s what we call our grandma—told me a story about how she wanted to start learning English after arriving to Montreal, in the late-60s. Her status was still only as a visitor in the country since it was only her husband who had a working visa. So, Immigration couldn’t let her find work. But she was allowed to take up a course. And so, when she went to the unemployment office downtown one Monday, she told the man at the entrance that she wanted to enroll in an English course. “Mais, madame,” said the man, “vous parlez très bien français. Pourquoi avez-vous choisi l’anglais? Pourquoi pas un cours de cuisine ou un cours de secourisme?” But that’s not what Mammie wanted. “Non,” she said. “Parce que je veux apprendre l’anglais.”

Haitian settlement in Quebec has been going on since the mid-60s. The autocratic rule of François Duvalier in Haiti caused thousands of its elite to seek refuge in countries like Canada. And, since French is Quebec’s dominant language, most Haitians, like my own family, came to the province knowing they’d have an easier time assimilating to its culture. In the last sixty years, hundreds of thousands of Haitians have settled in Quebec, making them the largest national community of African-descent in the province. Yet, because of this, the Haitian identity is often severed from that of a Black one. As Délice Mugabo posits in “Black in the city,” ‘Haitian’ has become an “easily recognizable marker that stands outside ‘Black.’”

In the same vein, the author of “Se rat kay kap manje kay,” Christian Rioux, who is white, attempted to categorize Haitians outside the category of ‘Black’ and argued that for any Haitian to think themselves as Black would be regressive.

“Sometimes I fear that this proud and noble Haitian identity may be in jeopardy today,” wrote Christian Rioux (my translation). “Haitians have nothing to gain from swapping their national identity for racial house arrest.”

The most glaring issue from Rioux’s piece was the decision to speak on behalf of a group of people without so much as hinting at the author’s own bias. Furthermore, it was quick to unify Haiti and Quebec’s struggle for sovereignty, explaining that one is “poor and free” and the other “always seeking freedom despite its opulence.”

Even at the height of anti-racism protests last summer, this type of opinion piece was surprising to me. It was hard to believe that a piece with such overt signs of racism could rise out of an extensive approval process of a major publication, like Le Devoir.

This one time back in high school I was eating lunch with two of my friends. They were part of the small minority in our school that came from French primary schools. So was I, technically. But because of my upbringing, I had always considered myself an anglophone primarily. Anyway, one of them was telling us about how he got into a fight in a hockey game the previous night, with a Black dude. “S’tai un géant,” he said. “Le nègre était sept-pieds-deux, j’te jure.” Well, I just looked at him. And he, noticing the sudden imbalance of enthusiasm on my part, began to explain himself in English. “That’s not what it means in French, you know?”

Rioux’s piece circulated on Twitter and Facebook and quickly got the attention of Montreal’s Haitian community. The following week, in response to Rioux, a collective letter signed by over fifty Haitians was released by Le Devoir. The letter, entitled “Une image toxique et fausse de l’essence même de notre identité” (“A toxic and false image of the very essence of our identity”), immediately denounced Rioux’s piece for his Machiavellian rendering of the Haitian identity and criticized the publication for perpetuating an anti-Black narrative. Later that same day, Brian Myles, director at Le Devoir, issued a statement of regret, writing that it had been the publication’s goal to demonstrate the complex realities of Quebecois society, even as it applies to “the Haitian community and other groups in minority or precarious situations.”

It made matters a little better, seeing Le Devoir pass the mic and let the community speak on its own behalf. Yet, there was no retracting Rioux’s contribution to an antiquated version of French-Quebec, one that conflated sovereignty with French dominion as its ‘national project’. But that is not the Quebec I know. Still, in doing so, Le Devoir only perpetuated a nationalist sense of self-entitlement that borders us from the rest of the country.

This one instance of anti-Blackness is a symptom of Quebec’s denial in recognizing Blackness as part of its constitution. Back when it was New France, many of the province’s prominent figures had a hand in governing Haiti before it fought colonial power and won its freedom and became the first Black republic in history. The repercussions of this are still felt today whenever Haitians are forced to stand up for themselves against the Eurocentric current.

But, without the capacity to read in French, all of this goes unnoticed. In Quebec, only English-French bilinguals can interpret the divisive attitudes reflected in our media. While still a minority to the rest of the country, French Canadians make up most of Quebec’s population and its readership. How severely Christian Rioux’s opinion is shared with the rest of the province is hard to gauge. But this racist ideology speaks of a larger system of dominance that is organized through agencies of social and cultural transmission, as seen in mass media, academia, religious doctrines, art, etc. If we can translate it, we can see how racism is reflected and regenerated through the very language around us.

In the several months since Rioux’s piece, I have often asked myself if it would have gotten more attention if it had been written in English. It probably would have. But I also believe no English media would have even considered publishing something of its kind.

Which is not to say that the piece reflects some sort of popular opinion within the Francophone community. On the contrary, the zenith of Quebecois nationalism has long since passed. Which is what makes Rioux’s point about the regression of Haitian identity so absurd. But, remove all its unsubstantiated claims and grating platitudes, the piece demonstrates the provincial nightmare of erasure. If we were really about the “preservation” of language we would have made better attempts at reviving ancestral Indigenous languages, which were here much before either of our colonial dialects. Fundamentally, it is a matter of knowing when your voice is not what is needed, or when it is.

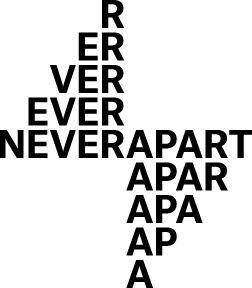

But, I suppose by expressing this in English I might be choosing a side. But I don’t think that’s what bilingualism means. It’s about coexistence, democracy. This is my internal voice and it looks like this.

There is little incentive for media outlets to develop their perspectives since most of these issues are very new. Quebec’s separatist modes of journalism are quickly proving themselves limited by monolingual attitudes. Quebec is a bilingual province, and its media should reflect that and be more inclusive.

In 2016, Anita Li wrote “How we talk about race,” in which she discussed the various ways Canadian media has failed to recognize diversity since the country often celebrates itself as being “multicultural.” Li, however, expressed excitement for non-traditional journalists innovating the field. “Born as start-ups, new media outlets also have non-traditional workplace cultures, including flatter hierarchies.”

It’s become a matter of knowing where to look. When it comes to bilingual Quebecois journalism, it is few and far between. Still, Twitter and Instagram accounts like @defundthespvm and @wokeorwhateva can translate content between French and English without losing any of its audience. This type of journalism is more inclusionary for many reasons. But, put simply, it allows us to occupy spaces that reflect the voices we hear in our schools, workplaces, or anywhere else that isn’t limited by one language.

About the Author

Nicolas André is a Haitian-Canadian son, a fading professional model, and an aspiring writer. Originally from the Laurentides region of Quebec, he has recently moved to Montreal. There, he occasionally visited his grandmother, who often used her Macaroni au Gratin as a Trojan horse for her stories of Haiti during the Duvalier-era. He has recently disappointed her by becoming vegan. He is currently studying Creative Writing and English Literature at Concordia University and writing for Collective Culture. You can watch him procrastinate from writing here: @pitiniki

Wawww…

I am so proud of my son, but now of the mature writer he has become. Looking forward to read more.