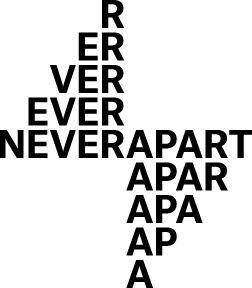

Evergon: A Conversation with a Canadian Legend

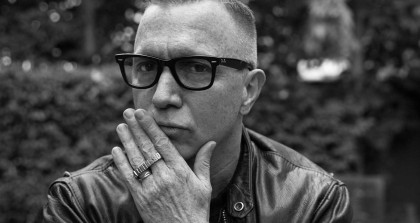

Walking into Evergon’s home in HoMa is like entering a kind of sanctuary. There is a sacred and magical energy that permeates the air. There is a buzz of creativity. You can sense instantly that this is a home full of life, where the imagination is free to run wild.

Everywhere you turn there is something to see—jars of spices, fairy ornaments, potted plants, and, of course, art. Most of the art that hangs on the walls of Evergon’s home are pieces made by his former students. In case you don’t know, Evergon is an internationally renowned photographer, whose career now spans five decades. He is known for his pioneering techniques in photography and his revolutionary exploration of gender and sexuality. Arguably his most well-known work is a series of larger-than-life nudes of his mother, done in 2001. It is a series he never actually wanted to create; it was his mother, Margaret, who he describes as being flirtatious with the world, who desperately wanted to be photographed. The photos and the beautiful, must-see documentary, Margaret and Evergon, that was made about their relationship, have become the touchstones of his legacy as one of Canada’s premiere artists. I have to admit, I knew little about Evergon and his work before our interview, but I was honoured and delighted to discover an artist and person of great generosity and kindness; a free spirit with an air of mischief and great concern for the state of the world.

Tranna: Early on in your career, you ditched your birth name and adopted the name Evergon. What did giving up your birth name mean to you?

It meant liberation, being able to let go of a certain history. Through the years, when I wanted to do other projects, the name became Celluloso Evergonni, Eve R. Gonzales, Egon Brut. And right now we’re playing with a new one (laughs). All the names are mutations of Evergon. Each one of the personas had their own clothes, their own camera, their own bio, their own identity. I used to joke, but it was basically true, that if I got stuck in a project or just bored, I could move to the other persona and do that work for awhile and that usually brought me back to where I wanted to be with the main body of work.

A lot of your work deals with the social construction and expression of gender, especially masculinity. How do you define masculinity?

I don’t think I’ve ever really defined it. In my life, I’ve played out many roles. I’ve been the country queen in the kitchen, chopping wood, using a chainsaw in a skirt or a dress. For me masculinity has always ricocheted.

There’s this weird moment right now with many gay white males pushing for this conservative masculinity in the way they present themselves photographically on social media and dating apps. It’s a kind of aggressive masculinity that seems to want to supress the feminine and the ethnic…

Well that ain’t me, babe (laughs). But the middle class gays have always been that way. The one thing that has always bothered me about gay politics is that once the middle class whites got what they wanted, which was two and a half cars, two and a half husbands, and kids, and a dog, and whatever, they stopped being political. How do you motivate the white middle class to care about the fringe? If I knew, it would have been done before now (laughs).

T: In regards to gay rights, within your lifetime, what do you think has really changed?

The word gay is out of the closet. It will be very hard to put it back. I think that’s the biggest thing. The world knows we exist. Before it was usually just law enforcement that knew we existed and they worked to make us non existent. I think if the truth was ever known about the Kinsey report, and we need to know, it’s more than one out of ten. I would think it’s a good half of people who have experienced gay relationships or gay sex or … I think America wasn’t even ready for one out of ten. I think a lot of the hate that we’re seeing is self-hatred, aimed back at us because we are the examples. It’s an interesting time. I realize I may have to fight the same battles over again.

Do you remember the first piece that you created that made you think, “this is art. I’m an artist”?

Let me back it up even further. I came out of the womb thinking, “I’m an artist.” And by three I knew I was going to be an artist. I had real support from my mother and my grandmother. When I got to middle school and they said, “oh you can’t be an artist, that’s not a career,” my grandmother told me: “Whatever you do, it is art. Don’t let them kid you.”

It seems like your childhood was defined by very strong women who wanted liberation.

And strong men.

Strong men but in the opposite direction. Your grandfather was extremely physically violent towards his wife and his children, to the point where he almost killed them. But the women in your life managed to survive…

And they still had the babies. That’s more power than any man has, as far as I’m concerned.

The brilliant documentary, Margaret and Evergon, is focused on your relationship with your mother, but what was your relationship like with your father?

Terrible. My father beat me a lot. I think my father felt that I took the love of my mother away from him. For any excuse, without even questioning if something was true or not, I usually got beaten.

Did you have any feelings of love towards him?

I did have feelings of love and I did want to be loved by him, but I could never satisfy him, regardless of what I did. So there was no point. You learn at some point to…

Cut your losses?

Cut your losses and find another man (laughs).

My favorite story in the documentary is the one about the raid that happened in your town, where a bunch of drag queens were arrested, and your mom went to go bail them out and drove each of them home. At the end of that crazy night, she managed to sneak back into bed without your father even realizing she was gone.. What did it mean to you, as a kid, to see your mother in action that way?

She was pretty well Joan of Arc. She was Queen Elizabeth I. She was a gutsy lady. And the kids knew that they could come and talk to her. We even had some kids live with us because their parents had thrown them out, until Margaret could get them back into the house and meet with the parents. She would say, “so you know more about your kid today than you did yesterday, what’s the problem? Your relationship should be better.” She was way ahead of her time.

What’s your fondest memory of her?

You can’t do that! (laughs) I think everyday. We lived the last six years together, here. And she could be difficult, but hey, she was in her eighties and nineties. The best thing about her is that she never lost her humour and she never lost her marbles.

How did your life change after her passing?

Depression, alcohol, falling apart, rebuilding. But I have to say, my partner, Roberto, died in 2000, and we had been together for 22 years. He had an aneurism in the brain. He was there one day and gone the next. And so at that point I had gone into mourning and I never came out of mourning. When Margaret died, the mourning just intensified. Now I’m not in mourning. Right now my life is great.

When you look back at your life, through your work, from the early days to what you’re creating now, is there a narrative that emerges?

It’s all the same.

What is the same?

I just think I have an incredible drive to create. There’s something here all the time to entertain me. Entertaining myself has always been what I’ve done. Right now I’m working with Jean Jacques Ringuette on four different bodies of work. He was actually a student of mine in 1978. We’ve had this love/hate affair for 40 years. We’re very much in tune with each other. He tends to, how do I say this…over clutter? And I have a need to tidy. We sort of keep each other in check. We push each other’s extremes. And it’s just a pleasure. I don’t like working alone.

What’s currently inspiring you artistically? What or who is your muse?

The house. I still don’t have great mobility, so when you can’t go out of the house, the house and memories become your impetus. And anyone who comes to the house, so watch it, kid (laughs).

Conversation avec une légende Canadienne

Entrer dans la maison d’Evergon dans Hochelaga-Maisonneuve fait l’effet de pénétrer dans une sorte de sanctuaire. Une énergie sacrée et magique imprègne l’air, qui bourdonne de créativité. On sent immédiatement que c’est une maison débordante de vie, où on peut laisser libre cours à son imagination.

Il y a des choses à regarder dans chaque recoin: des bocaux d’épices, des figurines de fées, des plantes en pot et, bien sûr, de l’art. La plupart des oeuvres d’art accrochées aux murs de la maison d’Evergon ont été faites par ses anciens étudiants. Au cas où vous l’ignoriez, Evergon est un photographe de renommée internationale, dont la carrière s’étend sur cinq décennies. Il est reconnu pour ses techniques de photographie innovatrices et son exploration révolutionnaire des genres et de la sexualité. Son oeuvre la plus connue est sans doute la série de nus plus grands que nature de sa mère, réalisée en 2001. Il n’avait jamais voulu créer cette série, c’est plutôt sa mère Margaret, qu’il décrit comme flirtant avec le monde, qui souhaitait désespérément être photographiée. Les photographies et Margaret and Evergon, le superbe documentaire portant sur leur relation, sont devenus partie intégrante de son héritage en tant qu’un des plus grands artistes canadiens. as one of Canada’s premiere artists. Je dois admettre que je connaissais peu au sujet d’Evergon et de ses oeuvres avant notre entrevue, mais j’ai eu l’honneur et le plaisir de découvrir un artiste et une personne d’une grande générosité et gentillesse; un esprit libre à l’air espiègle, très préoccupé par l’état actuel du monde.

À vos débuts, vous avez largué votre nom de naissance pour adopter le nom Evergon. Qu’est-ce que cela représentait pour vous?

Ça signifiait un affranchissement, pouvoir laisser aller une certaine histoire. Au fil des ans, lorsque j’ai voulu faire d’autres projets, le nom est devenu Celluloso Evergonni, Eve R. Gonzales, Egon Brut. Et en ce moment, on s’amuse avec un nouveau (rires). Tous les noms découlent d’Evergon. Chacun des personnages avait ses propres vêtements, son appareil photo, sa biographie, sa propre identité. J’avais l’habitude de blaguer, mais au fond c’est vrai, si j’étais coincé sur un projet ou je m’ennuyais, je pouvais passer à un autre personnage et travailler sur ses oeuvres. Ça finissait habituellement à m’amener où je souhaitais être avec le projet principal.

Beaucoup de vos oeuvres portent sur la construction sociale et l’expression de genre, particulièrement la masculinité. Comment définissez-vous la masculinité?

Je ne crois pas que je l’ai réellement définie. J’ai joué beaucoup de rôles dans ma vie. J’ai été la queen champêtre dans la cuisine, coupant du bois en jupe ou en robe, une tronçonneuse à la main. Pour moi, la masculinité a toujours eu un effet ricochet.

On remarque un drôle d’élan en ce moment, avec un grand nombre d’homosexuels blancs qui prônent une masculinité conservatrice dans la façon dont qu’ils se présentent en photo sur les médias sociaux et les applications de rencontre. C’est un genre de masculinité aggressive qui semble vouloir étouffer le féminin et l’ethnique…

Et bien, ça c’est pas moi, bébé (rires). Mais la classe moyenne a toujours été comme ça. La chance qui m’a toujours ennuyé des questions politiques sur l’homosexualité est que dès que les homosexuels blancs de la classe moyenne ont eu ce qu’ils voulaient, soit deux voitures et demi, deux maris et demi, les enfants, le chien, etc., ils ont cessé d’être politisés. Comment peut-on inciter la classe moyenne à se soucier des groupes marginaux? Si je le veux, ça aurait été fait depuis longtemps (rires).

En ce qui concerne les droits des homosexuels, qu’est-ce qui a changé au cours de votre vie?

Le mot gai est sorti du placard. Ça sera très difficile de l’y remettre. Je crois que c’est la plus importante. Le monde connait notre existence. Avant, il n’y avait que les forces de l’ordre qui savaient que nous existions, et ils se sont efforcés à nous faire disparaître. Si nous connaissons un jour la vérité à propos du rapport Kinsey, et nous avons besoin de la connaître, c’est plus qu’une personne sur dix. Je pense plutôt qu’au moins la moitié des gens ont déjà eu des relations homosexuelles … Je pense que l’Amérique n’était même pas prête à une sur dix. Je crois qu’une bonne partie de la haine qu’on voit est de la haine de soi, qui nous est redirigée parce que nous sommes les exemples. C’est une époque intéressante. Je me rend compte que je vais probablement devoir mener sans cesse les mêmes batailles.

Vous rappelez-vous de la première pièce que vous avez réalisée et qui vous a fait dire, C’est de l’art. Je suis un artiste?

Permettez-moi de remonter encore plus loin. J’étais à peine sorti du ventre de ma mère que je pensais déjà Je suis un artiste. À l’âge de trois ans, je savais que j’allais devenir un artiste. J’ai reçu un réel soutien de ma mère et de ma grand-mère. Lorsqu’ils m’ont dit à l’école primaire qu’être artiste n’était pas une carrière, ma grand-mère m’a dit: y grandmother told me: Tout ce que tu fais est de l’art. Ne les laisse pas te raconter des histoires.

Il semble que votre enfance ait été définie par des femmes fortes qui voulaient la libération.

Et des hommes forts.

Des hommes forts, mais dans le sens inverse. Votre grand-père étaient extrêmement violent envers sa femme et ses enfants, à tel point qu’il les a presque tués. Mais les femmes de votre vie ont réussi à survivre…

Et elles avaient quand même les bébés. c’est davantage de puissance que n’importe quel homme, en ce qui me concerne.

L’excellent documentaire Margaret and Evergon porte sur la relation entre votre mère et vous, mais qu’elle était votre relation avec votre père?

Terrible. Mon père me battait souvent. Je pense que mon père croyait que je lui volais l’amour de ma mère. Pour tout prétexte, sans se demander si quelque chose était vraie ou fausse, il me battait.

Ressentiez-vous de l’affection à so égard?

J’avais de l’amour pour lui et je voulais qu’il m’aime, mais je ne pouvais jamais le satisfaire, peut importe ce que je faisais. C’était sans intérêt. On doit apprendre à…

Éponger ses pertes?

Éponger ses pertes et trouver un autre homme (rires).

Mon histoire préférée du documentaire est celle du raid qui a eu lieu dans votre ville, lorsqu’un nombre de drag queens ont été arrêtées et que votre mère a payé leurs cautions et les a reconduit à la maison. Au terme de cette folle nuit, elle a réussi à se faufiler au lit sans que votre père n’ait remarqué son absence. Qu’est-ce que représentait que de voir votre mère en action, pour l’enfant que vous étiez?

Elle était pratiquement Jeanne d’Arc. Elle était Reine Élisabeth. Elle avait du coeur au ventre. Et tous les enfants savaient qu’ils pouvaient venir lui parler. Nous avions même des gamins qui vivaient avec nous, parce que leurs parents les avaient mis à la porte, jusqu’à ce que Margaret puisse parler à ces derniers et faire revenir les enfants. Elle disait aux parents, « vous en savez plus aujourd’hui à propos de vos enfants que vous n’en saviez hier, quel est donc le problème? Votre relation devrait être meilleure. » Elle était vraiment en avance sur son temps.

Quel est votre meilleur souvenir d’elle?

Vous ne pouvez pas faire ça! (rires) J’y pense chaque jour. Nous avons vécu ici, ensemble, pendant les six dernière années. Elle pouvait être difficile, mais elle avait plus de quatre-vingt-dix ans après tout. La meilleure chose chez elle est qu’elle n’a jamais perdu son sens de l’humour et qu’elle n’a jamais perdu la tête.

Comment a changé votre vie après son décès?

La dépression, l’alcool, tomber en miettes, se remettre sur pied. Mais je dois le dire, mon conjoint Roberto est décédé en 2000, d’un anévrisme au cerveau. Nous étions ensemble pendant 22 ans. Du jour au lendemain, il n’était plus là. À ce moment-là, j’étais déjà en deuil et je n’en suis pas sorti. Lorsque Margaret est morte, mon deuil s’est intensifié. Je ne suis plus en deuil maintenant. Ma vie est belle présentement.

Lorsque vous vous retournez vers votre passé, vers vos premières oeuvres jusqu’à ce que vous créez maintenant, y a-t-il un tissu narratif qui ressort?

C’est la même chose.

Qu’est-ce qui est pareil?

Je crois que j’ai simplement un formidable besoin de créer. Il y a toujours quelque chose ici pour me divertir. Me divertir, c’est toujours ce que j’ai fait. Je travaille présentement avec Jean Jacques Ringuette sur quatre séries d’oeuvres. Il était un de mes étudiants en 1978. Nous avons une relation d’amour-haine depuis 40 ans. Nous sommes très en phase l’un avec l’autre. Il a une tendance, comment dire, au surdésordre?! Et j’ai besoin d’ordre. Nous nous régulons mutuellement. Nous nous poussons à aller plus loin.. C’est un vrai plaisir. Je n’aime pas travailler seul.

À l’heure actuelle, qu’est-ce qui vous inspire artistiquement? Qui ou qui est votre muse?

La maison. Je n’ai toujours pas une très grande mobilité, alors lorsque sortir de la maison est impossible, la maison et les souvenir deviennent votre élan. Et tous les gens qui viennent à la maison, alors attention! (rires).

View Comments

No Comments (Hide)