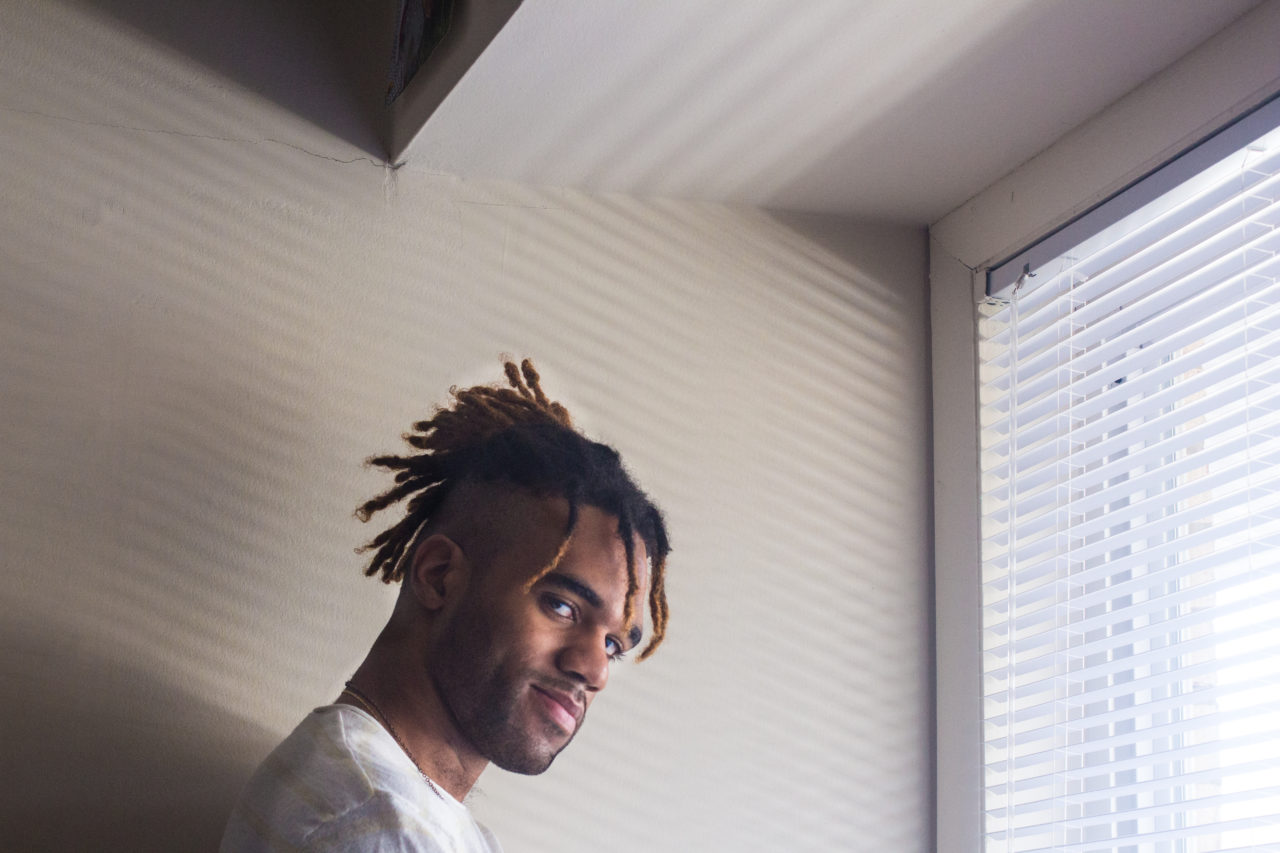

Mikael Owunna: Reaching Beyond Limits

Never Apart, along with the richly diverse cultural communities of Montreal, have continued to provide opportunities of experience and learning, focusing on new alchemical mergings through art openings and vernissages, film screenings and music performances, workshops and seminars, along with ever-growing recognition for these events since NVA’s inception in the summer of 2015. The Massimadi African and Caribbean LGBT Film Festival, is just one of those happenings weaving a rare mix of film installations, photographic art, social gatherings and community building. Celebrated and produced annually by African Rainbow, this year’s festival will highlight the premiere of Nigerian-Swedish-American photographer Mikael Owunna’s first exhibition, gracing the walls of the NVA Galleries throughout the Winter Season.

Owunna creates photography stemming from a great love for it. Raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania yet based in Washington, D.C., his upbringing provided him with a first hand experience of how the intersection of heritage and personal identity can often times conflict. “I do this work because I love it, because I live it, it’s who I am,” states Owunna. “I am a queer Nigerian person and grew up feeling that those two things were irreconcilable. I couldn’t be who I am, because I was LGBTQ and African.” Facing incredible abuse and homophobia in African spaces, including being put through multiple exorcisms in Nigeria during family trips to “drive the gay out of me”, in the United States, Owunna faced racism and a constant barrage of anti-blackness that threatened his life every single day. “This is particularly the case in white LGBTQ spaces, which make it abundantly clear that I am not seen as human there because I am black.”

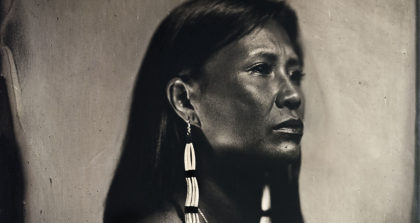

Owunna felt he had to build his own home for himself, a space of healing where he could be black, African, queer and whole. “A space of emancipation, liberation, freedom. That is why I do this work, for healing, for peace of mind, for my own sanity and long term growth. It has freed me from the space I was in just a few years ago where I was surviving but not living, if that makes sense.” Now, Owunna walks in the light of his own truth boldly, and knows it is because of this work. Inspired by Zanele Muholi’s work on black lesbians in South Africa, it revealed to him his first mirror of what queer African life can look like and brought him to tears. “It’s because of the amazing LGBTQ African people I have met since then, creating and building community across the world. These people have shown me what it means to be free, to love every part of yourself and your identity. They inspire me to heal, they teach me how to be me, they taught me how to be free. It has been liberating and one of the most important experiences of my life.”

Owunna began photography eight years ago following college. What began as an off-hand conversation with a friend about taking pictures while they studied abroad in Oxford, UK, quickly grew into a passion when he realized he had a knack for it. “With just a few weeks of practice I was already shooting better than people in my program who had been doing photography for years. I didn’t begin to see photography as an art form until years later when I went to Taiwan and worked alongside Prof. Christine Yeh of USF with aboriginal students there, teaching photography as a way to empower themselves and tell stories of their community through art and story telling. This project was featured in a full floor exhibit at the National Taiwan Museum in 2014.”

His photo series, ‘Limit(less)’, has allowed Owunna to focus on story telling and how every part of the frame fits into the narrative. “Also, understanding that photography is not ‘objective’. How incredibly careful you have to be as a photographer when telling the stories of people from marginalized communities. Even for me as someone in the community, with multiple dimensions of privilege of my own.” Owunna is obviously passionate, which he feels has been key in bringing him to the inner space he has now found within himself. New to the Never Apart space, he is excited about this being the first time his work will be exhibited. “It has been a dream of mine for years, and kind of surreal seeing it happen. I feel so blessed, but hard to believe in some ways. It means so much to me to see it get recognition.”

Through a friend, Owunna heard about the Massimadi Festival, and as he had planned to come to Montreal to shoot for Limit(less), he also returned to speak at the World Social Forum about the exhibit, and again during Pride as well. There, he met Laurent Maurice LaFafontant from African Rainbow, and learned about the work being done by Arc-en-Ciel d’Afrique. “Fast forward, and here we are. Black queer community is amazing. The way we love and support each other is such an inspiration for me,” says Owunna, who shares that the response from the LGBTQ African people who have seen the images has been overwhelmingly positive. “I think it also shows how much of a hunger there is for images like this. To see ourselves when we are so used to being invisible. I hope that more projects like this are created, there are so many stories to tell and we are such a beautiful community.”

In terms of special moments, the entire process has been life changing for Owunna. “It’s hard for me to point to a specific moment, but I’m happy when people participate in the project and love the pictures. I am most interested and excited in what black and African LGBTQ people get out of the work, and to see how it translates into physical spaces and can bring together community as it pushes forward conversations about African, black, and LGBTQ identities in that forum.”

Mikael Owunna: Dépasser les limites

Au même titre que les communautés culturelles diversifiées de Montréal, Never Apart continue d’offrir des possibilités d’expérience et d’apprentissage en mettant l’accent sur de nouveaux mélanges alchimiques, à l’aide d’expositions et de vernissages, de séances de film et de prestations musicales, d’ateliers et de colloques, ainsi qu’une reconnaissance pour ses événements qui ne fait que grandir depuis ses débuts à l’été 2015. Massimadi, le Festival des films et des arts LGBTQ+ afro-caribéens, est notamment un de ces événements, constitué d’un mélange captivant d’installations cinématographiques, d’art photographique, de rassemblements sociaux et de renforcement des communautés. Produit annuellement par African Rainbow, l’édition 2017 souligne la première exposition du photographe nigériano-suédo-américain Mikael Owunna qui aura lieu à la galerie Never Apart dans le cadre de leur saison hivernale.

Les photographies de Owunna ont à la base l’amour qu’il a pour cet l’art. Élevé à Pittsburgh, en Pennsylvanie, et vivant maintenant à Washington, son éducation lui a permis de voir de première main comment le croisement les traditions et de son identité personnelles peuvent entrer en conflit. Je fais ce travail parce que je l’aime, parce que j’en mange, parce que c’est qui je suis, » déclare Owunna. Je suis une personne queer nigérienne et j’ai grandi avec le sentiment que ces deux facteurs étaient incompatibles. Je ne pouvais pas être qui je suis, parce que j’étais LGBTQ et africain. » Il a été victime d’abus et d’homophobie en Afrique, incluant avoir dû subir plusieurs exorcismes lors de voyages de famille au Nigeria pour que l’homosexualité me sorte du corps. Aux États-Unis, la vie de Owunna a chaque jour été menacée par un déluge incessant de racisme. C’est particulièrement le cas dans des espaces LGBTQ blancs, ce qui démontre clairement qu’on ne me considère pas comme un être humain parce que je suis noir.

Owunna a estimé qu’il devait se bâtir sa propre maison, un havre de guérison où il pouvait être noir, africain, queer et entier. Un espace A space of emancipation, liberation, de liberté. Voilà pourquoi je fais ce travail, pour faire la paix avec moi-même, pour ma tranquillité d’esprit, mon équilibre personnel ma croissance à long terme. Ça m’a libéré de l’espace dans lequel je me situais il y a quelques années, où je ne faisais que survivre, plutôt que vivre, si vous comprenez. Owunna marche maintenant dans la lumière de sa propre vérité et sait que son travail est en la raison. Il a été inspiré par les oeuvres de Zanele Muholi portant sur des lesbiennes noires en Afrique du Sud; ces images ont été pour lui le premier miroir de ce qu’une vie queer africaine pouvait être et l’ont profondément ému. C’est grâce aux merveilleux africains LGBTQ que j’ai rencontrés, qui bâtissent des communautés à travers le monde. Ces personnes m’ont montré ce qu’est d’être libre, d’aimer chaque facette de soi et de son identité. Elles m’inspirent à faire la paix, m’enseignent comment être moi-même et m’ont montré comment être libre. C’est une des expériences les plus importantes de ma vie.

Owunna s’est mis à la photographie il y a 8 ans de cela à la suite d’études collégiales. Une conversation au sujet de la prise de photo q’il a eue avec un ami alors qu’ils étudiaient à Oxford, au Royaume-Uni, s’est rapidement développée en une passion lorsque Owunna a compris qu’il était doué. En l’espace de quelques semaines seulement, je prenais de meilleurs clichés que des gens de mon programme qui faisaient de la photo depuis des années. Je n’ai considéré la photographie comme une forme d’art que des années plus tard, lorsque je suis allé à Taiwan et que j’ai travaillé avec Christine Yeh de USF pour enseigner la photographie à des enfants aborigènes du coin pour qu’ils puissent s’émanciper et raconter les histoires de leurs communautés. Cet projet s’est vu offrir un étage complet au National Taiwan Museum en 2014.

Sa série de photos intitulée Limit(less) a permis à Owunna de mettre l’accent sur la narration et la manière dont chaque partie de l’ensemble s’intègre dans le tissu narratif. Aussi, de comprendre que la photographie n’est pas objective. Qu’en tant que photographe, il faut être minutieux lorsqu’on raconte l’histoires de gens venant de communautés marginalisées. Même pour un membre de la communauté comme moi, avec de multiples dimensions de privilège. Owunna est évidemment passionné et ce qu’il attribue ce nouvel espace intérieur présent chez lui à cette passion. Nouveau à l’espace Never Apart, il est excité pour sa première exposition. J’en rêve depuis des années et c’est surréaliste que cela se soit concrétisé. Je me sens privilégié; j’ai du mal à y croire. Ça représente énormément pour moi que cette série soit reconnue.

Owunna a eu vent du Festival Massimadi grâce à un ami, alors qu’il avait prévu de venir à Montréal pour tourner Limit(less), il y est revenu pour parler de l’exposition au World Social Forum et également durant la Fierté. C’est là qu’il a fait la connaissance de Laurent Maurice LaFafontant, de African Rainbow, et a entendu parlé du travail accompli par Arc-en-Ciel d’Afrique. « Revenons au present et nous voilà! La communauté queer noire est incroyable. Le soutien et l’amour dont chacun fait preuve envers ses pairs m’inspire, » explique Owunna en ajoutant que la réaction des africains qui ont vu les images est extrêmement positive. Je crois que cela démontre l’étendue de la soif du public pour des images comme celles-ci. De nous voir alors que nous sommes tellement habitués d’être invisibles. J’espère qu’il y aura plus de projets comme celui-ci qui seront créés, car nous faisons partie d’une communauté qui est si belle et qui a tant d’histoires à raconter.

Quand il en vient aux moments marquants, c’est plutôt le processus entier qui a changé la vie de Owunna. « Il est difficile pour moi d’isoler un moment précis, mais je suis heureux lorsque des gens participent au projet et apprécient les photographies. Je suis particulièrement intéressé de savoir ce que les personnes LGBTQ noires et africaines en retireront et de voir comment il se concrétisera dans des lieus physiques et pourra unir la communauté en suscitant un dialogue sur les identités africaines, noires et LGBTQ.

View Comments

No Comments (Hide)