More Than A Party

Author’s note: In this article I make connections between the Rave parties I love and the spiritual practices I have read about in books and magazines. My intent is not to argue equivalency. I am not an anthropologist, a scientist, or an academic. I am a hard-partying DJ who likes to read and a white transgender woman attempting to put her decades of experience in the electronic dance music scene responsibly into historical context. My analysis is both salutary and critical.

[Content Warning: Triggering Language re: Transness, Racism, Colonialism, Intoxication and Self Harm.]

My father asked me once why I started going to Raves when I was so young. I told him that he didn’t raise me with religion, so the raves were something like my church. In 1994, when I was 18 years old, I had a powerful set of experiences at warehouse parties in Chicago which would shape my life in ways I could never imagine. Nowadays I am what is called a “lifer”; someone who knows they are powerless to quit raving and resigned to that fact. For some club culture is perhaps mere entertainment, but for others like me, the music and the culture are essential and central in our lives. For the initiated, Raves are more than parties.

The events which shaped my definition of Rave were sweaty group experiences of sustained dancing under conditions that most would consider an ordeal. These parties went all night, sometimes for days. The excessive volumes were a selling point. (1) Polyintoxication and use of psychedelics were the norm. Alcohol was discouraged. For many of us, Raving was the first and perhaps only actual lived communal spiritual experience we ever had. In my case as a transgender woman, the Rave experience helped me dissolve the culturally constructed gender assigned to me and define my identity. In simple terms, raving helped me see myself and allowed me to participate in a community outside of the dominant society. I used it to find myself and my friends.

Over the decades I have asked myself how a future anthropologist would describe Rave culture. I’ve spent the better part of my adult life staring at synthesizers, turntables and giant stacks of loudspeakers. These tools are creatures of 20th century innovation, but they are used to trigger a subjective ecstatic experience as old as the earliest humans. We think we are dancing into the future when we Rave, but it appears we are also dancing into the past. This article will explore possible connections between Rave culture and spirituality, focusing primarily on the toolkits of various kinds of magical healers.

R4R x Motherbeat Rave in Berlin. Photo by Eris Drew.

Trance Drumming & Durational Mixing

Ever tell someone you like house music and they respond in jest, “oh you mean, that boom, boom, boom music?” Even the most ill-informed critics of electronic dance music culture seem to understand that a repetitive drumbeat is at the center of Rave. It is the heartbeat of dance music. The bass drum is usually the loudest instrument in the mix on a dance record and at a party it can thump continuously without a break for hours (even days!) as DJs seamlessly mix records back and forth. Nowadays, a lot of popular music uses this beat, but that wasn’t always so. In the late 1960s and ‘70s, it was the disco remixers and party throwers, Black, Latinx and Italian queers, who emphasized the four on the floor beat through drumming, sound system design, djing and remixing (2). The disco rhythm section was inspired by R&B and Latin rhythms (3). Central to the sound was the influential drumming and production of the Philadelphia team of Black American musicians known as Baker-Harris-Young, the true architects of the “four on the floor beat” as it is sometimes called, who were sought after studio musicians and toured with band MFSB and Vince Montana’s Salsoul Orchestra (4).

In the early 1980s, when disco died in the States and the big studio production budgets disappeared, innovative Black musicians in Chicago, Detroit and NY started to use drum machines to create an even stronger and more highly synchronized bass drum pulsation without the need for human session musicians. The key music machines were the Roland 303, 808 and 909, which were originally designed as affordable rhythm and bass accompaniment devices for trained musicians who wanted to practice at home without the band (5). Black folks took this technology and repurposed it rather spontaneously. While drum machine music typifies ‘80s production in many styles, it was certain young Black house producers that stripped disco and electronic dance pop of its ornamentalism and focused their work almost entirely on repetition and trance tones. For an illustrative comparison, listen to Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” (6) followed by the first ever acid house record, Phuture’s “Acid Traxx.” Both use synths and a prominent four on the floor beat, but there is no melody in Phuture’s 12-minute minimalist epic. The focus in Acid Traxx is the central beat and trance-inducing resonances. In a DJ’s hands it is in a sense a tool, not a song with a chorus, verse and melody like most popular music.

There is a wonderful story which DJ Pierre, one of the original members of Phuture, has shared regarding the genesis of the house and acid scene in Chicago (6). Ron Hardy, the well-known legendary house DJ, played a lot of disco for his crowds and broke a lot of early house records. The first time he played Acid Traxx, it allegedly cleared the dance floor. As the story goes Hardy played Acid Traxx several times that same night and by the end of the party everyone on the floor was screaming, dancing extra hard and totally whipped into a frenzy by the track. It seems that what is now called “acid house culture” was sparked in this moment of transport and shared ecstasy.

According to commentators, the drum has “a role of the first importance” in ecstatic traditions including Shamanism (7). It is used for “Shamanic flight,” to summon spirits, and to “concentrate and regain contact with the spiritual world through which [she] is preparing to travel.” (8) It is the fast continuous beats which allow the participants to “experience non-ordinary reality” via a state of trance stimulated by rhythm (9). Although the science of trance drumming is underdeveloped and necessarily relies on testable hypotheses to advance its claims, there appears to be a connection between trance drumming and the brain’s theta waves as measured on an EKG (10). Sustained repetitive drumming lowers the brain’s operational frequency to 4-7Hz. The theta waves alter perception and cognition, allowing the practitioner to disconnect from ordinary reality and gain insight. Theta waves are connected with meditation, spiritual awareness, creativity, intuition, daydreaming and memories (11).

The drum was the center of my revelatory mystical experience in 1994. My best friend and I took LSD at a big Rave in Chicago. We danced into these huge speaker stacks for hours. Like the opening scene of the feature film 2001, we stared into the speakers like the monolith, looking for meaning in something we did not understand (12). As we danced, colorful symbolic geometries appeared in the blackness; self-transforming spinning mandala-like (13) forms. I had the feeling of flight, like I was at the party and somewhere else at the same time. After the party we were still tripping hard as we rode home in the back of a minivan. The air-conditioning was blasting and we started hearing the thump of the bass drum from the party in the oscillations of the fan and its motor. A modulated noise source like an air conditioner will sound like a musical pulsation if you listen to it long enough with the right focus. In the moments of clarity which followed, my friend looked at me wide-eyed, smiled and proclaimed it “the Motherbeat!”

It is difficult to put into English this part of the experience because what happened in that moment was a kind of gnosis (14), a moment of pure understanding between us and the world. I saw in that moment that the music was all around us. I understood that the beat which drives our music is something far more fundamental and mysterious than an ornament of culture. That there is something nurturing, healing, and nature-connected inside sound made even through “artificial” processes. And that the music could be used to accomplish a feeling of oneness. I saw the powerful illusion of culture for what it was, a gloss or artificial landscape through which we filter our actual subjective experiences. While drugs were a factor in my experience (and an important one as I will endeavor to explain below), the drumbeat was necessary. It was our conduit to the Other, the Mystery at the center of being.

The drumbeat at a Rave is, for the most part, continuous. DJs develop the technical skill of synchronizing records (or digital music files) using a tool on specialized turntables (or other playback devices) to control pitch and time. The way to increase the pitch of an analog recording is to speed it up. To make the pitch lower you slow it down. The DJ has to maintain an intense level of focus in a deep state of listening to keep the tracks in sync using a set of turntables. The mixer is used to blend the separate audio signals for each track and make the transition from record to record continuous and seamless (or to disrupt the transition in artistic ways with “creative eq” or by “cutting” or “scratching”). The perception of the Raver is that the party has an eternal beat. If repetitive drumming is indeed central to the experience of an ecstatic trance, Raves appear to represent a potent 20th century implementation of very old human technology.

The average length of a pop song is three and a half minutes, and that number appears to be shrinking (15). Compare the length of a popular song to a DJ mix which can flow for hours without interruption. Listening to durational music requires concentration and focus. Listening to music in this way can be seen as a meditation of sorts which leads to a heightened sense of mindfulness. Experimental 20th century composer Pauline Oliveros is perhaps most famous for her spontaneously generated compositions and ensemble performances inside a giant concrete underground cistern–a 2-million US-gallon empty underground water tank with a 45 second reverberation time (16). Her process of intense listening to all sound, not just “musical sounds”, enabled her to descend into the enclosed cavern with her friends and play the reverberations in the chamber as an instrument. On the recording, she transforms her beloved accordion into something beautifully unrecognizable using nothing more than a few microphones and the acoustics of the cistern. Oliveros described the technique of what she calls “Deep Listening”as such:

Deep Listening is listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear no matter what you are doing. Such intense listening includes the sounds of daily life, of nature, or one’s own thoughts as well as musical sounds. Deep Listening represents a heightened state of awareness and connects to all that there is. As a composer I make my music through Deep Listening. (17)

My perception of the Motherbeat in the air conditioner seems to be an example of the durational Deep Listening I did at the party focusing my mind enough to use the air conditioner to connect the Rave experience to “all that there is.” I have shared the so-called “dance floor” over the years with plenty of very serious Ravers who were not dancing because they either physically could not dance or preferred to behold the music without dancing. I think it is the experience of Deep Listening in a community that really matters for them. Dancing builds heats in the body, which may be of some use itself in attaining states of ecstasy (18), however the drum remains central (19). One of the key points I hope to make in this article is that the scene is about so much more than dancing, drinking and having fun.

Delicious mushroom chocolates given to Eris as a gift before a Rave. Photo by Eris Drew.

Psychedelics – Democratizing the Subjective Religious Experience

When I give presentations on my Rave experience, one of the first questions I am asked is, “do you need drugs to have the mystical experience you describe?” The simple answer is “no.” Anthropological evidence supports the conclusion that ecstatic states of trance can be accessed through various means. A principal authority relied upon in this article for its summary of ethnographic fieldwork, Mircea Eliade’s 1964 treatise “Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy,” contains numerous examples of spiritual traditions involving trance that do not rely upon psychedelics (20).

In fact, for Eliade, the use of psychedelics is viewed as a “crude” and “decadent” means by which to access the trance (21). For example, he views mushrooms use as a lazy form of shamanism in which practitioners become decadent, favoring the ease of the intoxicant over the hard work of other more powerful (sober) healers. Scholars like Eliade bring their misconceptions and prejudice with them as they assess the field work. I disagree with the argument that the use of psychedelics is in some way “decadent”, lazy or unnatural for the reasons below.

Psychedelic substances exist in nature and are part of it. The experience is not artificial in any real sense. The most popular psychedelic mushrooms grow in the feces of cattle and LSD was originally synthesized from ergot, a fungus that attacks rye (22). DMT is naturally occurring in many plants and is endogenous to the brain in at least some mammals (23). I do not think I would have had my Motherbeat Experience without taking these powerful natural boundary dissolvers. In 1994, I had no interest in consulting traditional healers or participating in the New Age movement. I was raised an atheist in a rationalist-materialist-culture. My sense ratios were altered by a lifetime of media consumption. And my ability to focus and concentrate was limited because I had no formal training in any ecstatic tradition. Psychedelics somewhat democratize the spiritual experience in the sense that the powerful subjective experience of a trance-like state is available to anyone with access to the substance. As psychedelic celebrity Terrance McKenna was fond of saying in so many of his lectures, with psychedelics you don’t have to sweep floors in a monastery your whole life to get the secret. You do not have to find a guru, or a master, and you don’t have to accept dogmatic religious cosmologies to see the mysteries. If we got Donald Trump to take three strong tokes of DMT he would probably trip whether he liked it or not.

While I expect many folks would find the notion of a teenager stumbling onto a mystical experience through drug culture irreverent, irresponsible or even disrespectful, my testimony is that these substances when combined with the intense drumming of a Rave, had the power in my life to produce a life-changing subjective spiritual experience (24). The focus at a Rave should be on harm reduction, not on dismissing the content and the very real importance of these subjective experiences in the lives of individuals and communities.

Psilocybin is the psychedelic component of “magic mushrooms”, including the popular Psilocybe cubensis. There are at least 20 completed or pending scientific studies of Psilocybin for therapeutic use (25). This research, however, is primarily a recent phenomenon. At the time I started Raving, research into these substances was effectively banned. In 1994, talking about these subjects openly was a risky choice. There was almost no mainstream discourse about these substances that wasn’t utterly infected with the false ideologies of the Drug War. In 2018, Michael Pollan’s book How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression and Transcendence was a New York Times #1 Bestseller. As it stands now, there is considerable scientific and clinical support demonstrating that psychedelics, in an ideal set and setting (26), can be powerful healing medicines.

Eris in mix for Interdimensional Transmissions in Detroit at their Movement Stage. Photo by Brendan Gillen.

MDMA and the Culture of Ecstasy

I first came across the idea of a Rave through media in the early 90s. I was drawn to Raves by the descriptions of these futuristic hippie gatherings circling through the popular media. The truth is that I was being sold a Eurocentric version of a Black gay dance culture that erupted from the very town I considered home, Chicago (27). The spread of House culture is inexorably linked to colonialism and colonialist histories. This fact fuels very legitimate scrutiny and challenge over white power structures in the electronic dance scene some 35 years after Ron Hardy put his dancefloor in a trance for the first time with “Acid Traxx.” MDMA, the drug known as Ecstasy, also played a significant role in the spread of house music outside of the gay Black culture from which it spawned.

A synchronicity manifested in the mid-1980s, because around the same time that the first House records were hitting record shelves as imports in Europe, MDMA became widely available for the first time in the underground. Although the drug was first synthesized by a German pharmaceutical company in 1912, it was not a well-known recreational drug until the second “Summer of Love”, the term used to describe the summer of 1988 when Rave culture exploded in the UK. The Drug-War-obsessed media grabbed the story and painted a grim picture of Rave for the mainstream news, which in turn fueled legislative and law enforcement action. For example, the press described MDMA as an “evil drug” (28) and the United States Government listed it as a Schedule I drug, the most severe classification for an illegal drug, which means that it has no accepted therapeutic value and possession carries the highest punishment (29).

Almost 30 years after the house explosion and the backlash against Ecstasy and the Rave scene (30), the FDA designated MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD as a “Breakthrough Therapy.” (31) The US government has since allowed MAPS, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, to proceed with Phase 3 trials (the final tests of a drug or therapy before it is cleared for use) under this rubric. Approval if the trials are successful is expected in late 2022 or 2023.

According to MAPS, MDMA may have the following potential: We are studying whether MDMA-assisted psychotherapy can help heal the psychological and emotional damage caused by sexual assault, war, violent crime, and other traumas. We are also studying MDMA-assisted therapy for autistic adults with social anxiety, and MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety related to life-threatening illnesses.

As a trans queer person who has experienced traumas, I found the oneness and ego loss I experienced at raves on MDMA extremely healing. The feeling is like a kind of universal empathy which extends to people you don’t know, people different than you, and importantly yourself. The impact when you are dancing is an openness to the emotional content of the music and a feeling of oneness with the people around you. That is the ideal of dance music, as imperfect and flawed as it is in actual execution because of power structures, inequality, racism, sexism, ableism and transphobia. These structures exist even if it feels like they fade away in the mental state catalyzed by the drug. Accordingly, for someone who isn’t grounded in radical politics, MDMA could look like a “cure-all” for society’s ills. As I have learned, the drug is no panacea, but MDMA does offer a glimpse of an improbable utopia whose lasting spiritual resonance can be a motivational force for change, healing and growth.

The reason I think MDMA is so powerful in the context of Rave culture is that it creates a sense of community on the dancefloor. Ecstatic rituals in most cultures appear to center around communities. The ritual serves a myth-making function for the group and solidifies community values. It is axiomatic that having intense experience with others binds you to them. In many cultures, specific rituals signpost coming of age and maturity. Personally, I have always felt like an outsider in the dominant society. I generally feel unsafe when I am around cisgender people, unless they are my most trusted allies and friends. For the set and setting of a Rave to be a positive experience for me, I needed to feel a base level sense of safety, belonging and acceptance. When on Ecstasy (if people were being descent, the party was not triggering, and everything was going okay), the things which divide us were in some sense visible as constructed modalities of oppression, violence, capitalism, and prejudice. So, on the drug I was able to relax enough to let the music into me and to dance the way I wanted to without fear of reprisal. My whole life I have been punished by others for my femininity, in ways ranging from gentle correction, to distrust, to outright bullying. Before coming out, suppressing and managing that aspect of self was a full-time job outside the Rave. Inside the music it felt different. I felt a sense of freedom, connection and wonder.

When people who experience marginalization by the dominant society feel unsafe at Raves or experience on the dancefloor the types of harassment they face in their everyday lives, it is a kind of blasphemy because they are in so many ways the source of the music, energy, and inspiration that fuels the scene. When these things happen to a person while they are under the influence of a drug like Ecstasy, the trauma can multiply because they are in an extra vulnerable, ego-dissolved state. People who throw events have a tremendous responsibility to the people who come. Anti-harassment policies are a lure on a stick if they are not enforced. For example, how is a BIPOC person supposed to have a positive spiritual experience at a Rave when white people are allowed to dance in feather headdresses and dashikis at festivals without challenge? How can a party claim to honor Rave if the promoter is not concerned about making the experience accessible to someone with mobility issues? The simple truth is that many of the players in the scene are rich white men with only the most tangential relationship to the communities of individuals existing on the margins of the dominant society who use the music to create art, find their friends, and heal.

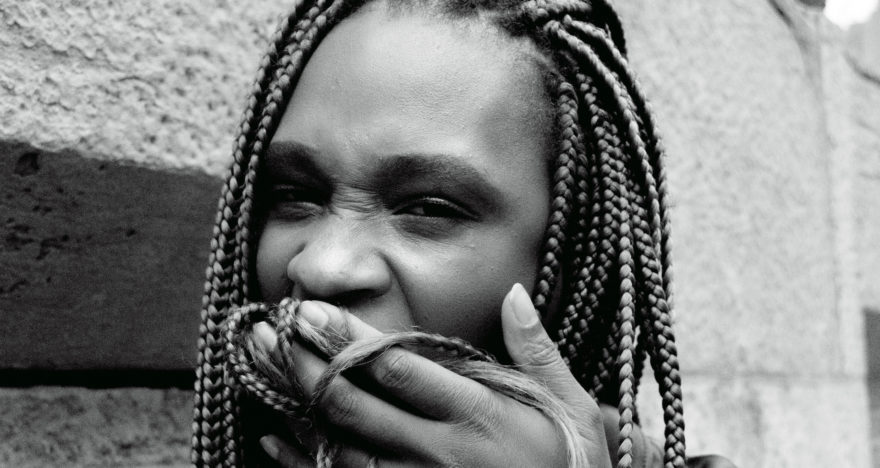

Rave Rain at 6:30 am after a ritual at Pickle Factory, London with CCL b2b Eris Drew. Photo by Eris Drew.

Alcohol

When I was in High School and I started raving I associated drinking with the jocks who bullied me (Do not feel sorry for me—a phoenix rose from those ashes!). I remember seeing alcohol at only one Rave I attended between the years of 1994 and 1996. I was told by other Ravers that hard drinking mixes horribly with psychedelics and MDMA. Drinking makes you feel more powerful and less empathetic. Whereas the drugs we previously discussed are used to dissolve the ego, alcohol does the opposite. That is probably why people like drinking so much in this society. Ego death is an incredibly vulnerable experience but drinking makes you feel invincible.

During the height of Rave culture, the jam-packed Hacienda club in Manchester had to close, in part, because everyone was so loaded on “E” that the bar never made money off alcohol (32). Nowadays almost every event I attend is fueled and financed through alcohol. My early Rave friends and I believed that drinking dulls the ecstatic mystical component of ecstasy and transforms the drug into more of a speedy deliriant. As I conducted research for this article, I could not find a single citation for this concept because the discussions I found center around the dangers of mixing alcohol with ecstasy, not the impact that alcohol has on the healing component of the substance. It appears that early Ravers had started to define a set of cultural rules around Ecstasy use which were quickly eroded. In my own story, by the late 1990s my focus had turned to clubs and I started drinking at events. I will address this time in my life in more detail in the next section of the article.

Directory Service x T4T LUV NRG Rave in LA. Photo by @Missingtextures.

Ordeal – Sleep Cycles, Polyintoxication, and the Hardcore Ethos

Many spiritual practices involve some type of ordeal. Fasting, exposure, and ordeal poisons are all well-documented techniques. An ordeal in a spiritual context can have multiple purposes, but it can be said as a general matter that a person puts their body through an ordeal in order to quiet the ego and focus the mind. In some cultures, the ordeal is a rite of passage. For many, Raving would seem like the opposite of an ordeal or ascetic spiritual practice. What does a fun night out have in common with a set of hard dedicational spiritual practices focused on reaching higher states through self-denial, overcoming pain and doing without? Indeed, many ravers have expressed to me over the years their belief that Rave is hedonic; a culture obsessed with seeking pleasure and avoiding suffering. And for some it is. But in my experience, ordeals are one of the most significant components of the spiritual Raver’s toolkit. A Rave goes all night, into the morning. It can last for days. Ravers disrupt their sleep cycles as part of their regular routine. Fasting during events is commonplace, although I suspect most Ravers don’t realize this is part of the magic. By way of comparison, Ayahuasca preparations are traditionally administered after a period of fasting to prepare the body for the experience. Terrace McKenna advised that mushrooms should always be taken on an empty stomach, so the trip comes on fast and strong. Ravers will dance for hours without food, and some never take a break. By the end of the party, a dancer is often dehydrated, empty and sleep deprived, while at the same time elated, ecstatic, and renewed.

Many Ravers repeat this process every week, year after year, some for life. The toll on our bodies is hard. For a special group known for better or worse as “speaker freaks,” we damage our bodies with some degree of intentionality by placing them directly in front of the speaker stacks or inside the bass enclosures. The volumes at parties are undeniably too loud for safe listening, even with ear protection (which I of course recommend because it is at least safer). But many Ravers want to feel the Motherbeat move through us. We want to feel the wind coming out of the bass traps. We want to feel a sense of purification and renewal as our bodies are both punished and nourished by the soundwaves. We want to stare into the speakers like an oracle, beholding the sound and allowing a process of synesthesia to form visualizations in the black void, a perfect canvas for hallucinatory experiences.

I learned the techniques of speaker freaking at the “hardcore” parties in the Midwest. These parties featured high tempos and a subgenre of “hardcore” dance music imported from the UK which was built for intense raving. Tunes like Nino’s “Future of Latin” (33) feature extremely fast syncopated beats, synths that slice through the body, the pure ecstatic emotion of pianos, and impossibly re-pitched vocals. The Midwest had its own version of hardcore techno, which was more stripped-back and industrial. A classic from the era is Woody McBride’s “Techno Pagan Ritual” on the Minnesota hardcore label Communique (34). The hardcore partiers showed me their culture and their values through doing. I was drawn to them. A speaker freak moves to the front of the party. It is like the front line; the first point of human contact for the music. Their energy feeds back to the DJ as part of a beautiful, ineffable energetic cycle.

I hesitate to write the next section because it is not a practice I encourage. For many Ravers, poly-intoxication is the norm. While I abandoned this practice years ago, for much of my time as a clubgoer, I would experiment with combinations of drugs, some of them dangerous (35). While my first few years of Raving were focused on Ecstasy and LSD, drug combinations became normalized through clubbing and I eventually moved on to other things. Now when I go to a festival or club, many dancers have been drinking and taking a cornucopia of substances over the weekend. It isn’t unusual to see a bag of molly in one hand and drink in the other. At one point in my life a night could include heavy drinking, cocaine, and MDMA. To be honest these were difficult times for me and it is hard to write about, but I do not honor my true spiritual experience as a Raver if I do not discuss it. This is how I see it: I broke my body down so much during this period in my life so that I could in some sense destroy myself. In moments alone in delirium near death, I knew that the only way I could continue to live is if I let myself live an open life as transgender person. I had to let my culturally constructed adult persona die so I could come out and rebuild. In those states of delirious polyintoxication and disembodiment, I remember looking in the mirror and seeing myself. That might seem contradictory, but I think for a transgender person a certain degree of dissociation can be a tool. Everything had narrowed to a single point of focus that I could not ameliorate with intoxication. This drug induced delirium let me engage with my transness in ways I had never allowed myself. I was hiding and had withdrawn from every aspect of my normal life. I hit a breaking point, and after almost 4 decades on this planet I came out. As much as I never want anyone to go through what I went through—or what I put my loved ones’ through—I know that without these experiences, you would not be reading this today. A more nurturing scene focused on integrating the Rave experience into everyday life, much in the way an Ayahuasca ceremony is a community experience which starts before the event and continues after it, might have been a gentler path.

Eris’s studio for solitary work in New Hampshire, USA. Photo by Eris Drew.

Private Healing Rituals Create Healing Art for the Dance Floor

Much of the discussion of Rave centers around the parties and the communities that gather before them (36). But so much of electronic dance culture is informed by private experiences. My DJing, which in the last 2 years took me to 30 countries, reflects the thousands of hours I spent alone or with a friend, mixing records at home, dancing or not, adorned, and experimenting with substances. My music production reflects decades of solitary work which I started in my early teen years. Before I came out, the only time I would wear the clothes I wanted to wear was during these private rituals. For years I would put on a dress and let the power and beauty of the act be expressed in my music and the movements of my body. Eliade’s definition of a healer suggests a connection between magical healers and the electronic musicians I know. The “magician, the medicine [person] or Shaman is not only a sick [person], [they are] above all, a sick [person] who has been cured, who has succeeded in curing themself.” I believe that the power of the healing art presented at a Rave represents the private healing work of individuals.

Adornment, Transness, & Transubstantiation

Costume and adornment are a part of the healers’ toolkit in many cultures. According to Eliade, on the most basic level, the costume “represents a religious microcosm qualitatively different from the surrounding profane space.” (37) For example, in certain cultures healers adopt the costume of animal gods or other spirits for rituals. For its part, “the costume transubstantiates the shaman, it transforms her, before all eyes into a superhuman being.” (38) Transubstantiation is a ritual act which changes the form or substance of (something) into something different. It is in this context that anthologists such as Eliade point out the power of “transvestite”, “androgynous” or “feminized” healers cross-culturally. (39) For a white European rationalist scholar like Eliade, would a 21st century trans woman’s act of wearing a dress during a ritual be in effect a magical mask? (40) It is a strange and triggering experience to read about people who might have been like me in some deep sense described in this way. However, we do not know these people being talked about. Gender is culturally constructed so we cannot really know how these people saw themselves. Were Eliade’s descriptions of these healers based on how he viewed gender, how they saw themselves, or how they were viewed by others in their community? These healers might utterly reject my understanding of my experience of gender or tell me that it simply doesn’t apply to them. They might say Eliade is basically correct in his assessment of their identity and role in culture.

For me, my expression of gender is not a mask—many transgender friends whom I’ve had conversations with also share this feeling. While I am and always have been a transgender woman, do people view my simple act of getting dressed for a show as an ecstatic technique of transubstantiation by which I magically become a symbol of something I am not? If I became, in some sense, magical when I wore dresses and make up, it was because I was disrupting power systems, transcending cultural limitations, and being myself. It was like letting out a power that was already there, not manifesting otherness through an act of transubstantiation. I do not view myself as transcending my nature, I view myself as transcending cultural programming and ideologically infected materialist models of gender and the body. It is, however, undeniable that my personal and radical understanding of my transition as primarily a social process is not in-line with the view of gender held by most of the people coming to my shows. Therefore, it is likely that outsiders to the experience view transgender DJs and musicians as performing in some sense a symbolic and/or radical act of transubstantiation.

I have viewed my success over the last few years as a transgender DJ and producer as a sign of positive social change. While that might be true in some respects, I am struck by the fact that I might have been drawn to DJing because of its connection to a traditional social role held by people that had in some sense an experience like mine. It is important to note in this context that the healer is a marginalized character. (41) For some healers who are touched by femininity, Eliade coldly posits that they “chose […] suicide.” (42) According to him, the other option is “initiation.” For the manang bali, the “command” to—in some sense—transition gender roles is accepted after it is received in dreams. For the Chukchee, the “command” comes from a ké let (spirit) which speaks from the body during an ecstatic trance ritual. (43) Could my perception of the beat in the air conditioner as “Mother” (a feminine beat) have been connected to my experience as a transgender person?

Glossolalia, Sound Poems, and Samples

While there are dance tracks which contain pop vocals, the typical house or techno track contains disembodied voices or no voices at all. Unlike Rock ‘n Roll, in which the personality of the vocalist is a major focus of the work and how it is presented (marketed), in house music the voices are often sampled and manipulated beyond recognition. Ravers make little jokes about what they think the voice is saying in a track because there are inevitable disagreements and we know that what we hear on a dancefloor can have little or no relation to the actual source of the vocal. For one commentator, this is a “Sonic Rorschach,” named for the well-known inkblot used in psychotherapy (44). Through the process of listening the original meaning of the vocal is obscured in favor of the listeners’ subjective interpretation. The manipulation of voices allows Ravers to view the content of our psyche as a reflection of what we hear in the music.

For the members of Dada, a European avant-garde art movement of the 20th century, sound poems, or “poems without words” were a useful way to destroy everyday language and return the voice to its pre-cultural, irrational, feeling-toned meaning; like a baby gleefully chirping away without syntax. Their poems were a metaphor for the devastation caused by WWI and a criticism of the deceitfulness of language and society. In a number of well-documented spiritual traditions, unknown tongues, so-called “glossolalia”, have a similar function of freeing the voice from cultural constraint. For example, in Pentecostal traditions, some members speak in glossolalia during the most intensely ecstatic climax of a religious ritual. The speech of an unknown language signals the transition of the speaker out of the cultural mode and into the presence of the holy spirit (45). It is notable that high doses of psilocybin and DMT can also stimulate a form of glossolalia during intoxication. Dance tracks often contain reorganized words or partial phrases without syntax. A lovely example is the “The Dub of Doom” mix of “Push the Feeling On” by Nightcrawlers. Despite the fact that the song has no complete words or syntax, the reorganized nonsensical vocal hook propelled the song from underground status to a worldwide radio hit.

As a trans person I have found a lot of freedom in the vocals of dance music. And that freedom extends beyond a spiritual release from syntactical meaning. Because so many of the records I play contain sampled voices, there is an irreconcilable ambiguity as to the gender of the speakers. For example, a voice could sound “male” to the listener, but without asking the vocalist their gender, how do we know? The voice could have been manipulated using pitch and time techniques. The original singer could be a trans woman. It is like the music is a reminder not to make those associations and assumptions against people you don’t know, or against people who are not there to speak for themselves. I would like to live in a world in which people do not assume they know my gender based on a crude formant analysis of my voice. It is a wonderful experience to play records containing different voices and mix them all together. Through sampling and collage mixing techniques, the relationship of gender to voice becomes unhinged.

Gender though is not all that becomes unhinged through sampling. When sampling disrupts racial histories, it is highly problematic. If sampling is disruptive of culture as Dada suggests, then it also is at times an instrument of oppression and anti-Blackness as it disrupts Black narratives. As just one example, there are some electronic dance tracks that sample Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have A Dream” speech. Dr. King talked in part about universal concepts in his speech, but his message was firmly rooted in Black justice and Black struggle. Contrast Black American artist Larry Heard’s (aka Mr. Fingers) tribute to Dr. King (46) with a listen to the trance tune “I Have a Dream” by white artist DJ Quicksilver (47). As I believe these examples show, it uproots meaning to use Dr. King’s message in a song about the freedom experienced clubbing when a white person creates or plays it. Therefore, the choices of DJs and producers should be informed by the anti-harassment analysis discussed earlier if Raves and the music associated with them are to be a true apparatus for healing and not further instruments of domination and oppression.

A View Towards the Future

Throughout this article I have proposed points of connection between Rave and other spiritual rituals and practices. The spiritual toolkit of Rave is an important part of why Ravers seek out these parties to heal. Unlike the other spiritual practices identified in this article, Rave is in its infancy. The energy sparked in the Black gay Underground clubs in the 1980s was quickly commodified and appropriated. The festival and big club culture which dominates the dance music scene today has adopted an “entertainment” model of raving with big personalities, flashy stages, corporate sponsorships, and a predominance of white straight artists in the spotlight. While many of the ecstatic tools of Rave are still present at these commercial events, we honor the roots of the scene by challenging the current status quo.

The music remains a powerful tool for transcendence, but the scene cannot harness its full healing potential without strong measures in place for harm reduction and anti-harassment. Intoxication is a free-for-all at many events. In this respect, the scene couldn’t look more different from a traditional spiritual ceremony utilizing intoxicants in which there is a cultural tradition of using the substance and great care is taken by practitioners to train in making preparations, picking plants, and dosing. Similarly, MDMA will be approved by the FDA, if at all, as part of a therapeutic complex, which includes an intoxication experience guided by a counselor.

Enforcement regimes have made it challenging for promoters to offer drug testing, but more and more events are taking on the legal risk. Groups like Dance Safe offer drug testing and groups like the Zendo Project offer counseling on-site for individuals having difficult experiences on psychedelics and other intoxicants. An Ayahuasca ceremony might give rise to a very challenging experience for an individual, but the practitioner (Shaman) who gave the medicine trains for years on how to help the individual through it. The spiritual lesson is an act of integration. For Ravers like me who set-out to crack themselves open using the available toolkit, integration could help prevent future self-harm and moderate attempts to reintegrate these experiences into everyday life. Anyone throwing parties can start to educate themselves and others involved by taking the online training in handling difficult experiences that is offered by the Zendo Project.

***

While club culture is entertainment for many, for certain people who seek out the experience, I hope I have demonstrated that it is so much more. It is hard to imagine my life without the music, without the special group of friends I have become close to through the music, and without the routine of sweating it out at a party. I continue to use mushrooms as a tool for transcendence, connection, and creation because I continue to get a lot from these experiences, and, after all, ecstatic healing is not a one-time thing. A lifetime of Raving might be hard on the body, but it is easy on the soul. My hope for the scene is that it will work to harness its healing potential in a way that respects the roots of the scene and the people who rely upon these parties as an essential ritual in their lives.

End note: I would like to thank my partner, lover and friend, Q, who offered valuable insight and suggestions that were incorporated into this work.

Top illustration by Samantha Garritano

Footnotes

(1) For example, Ravers attending “Pollination” on May 21st, 1994 were invited to “Frolic in the Phunk-E Phresh 40 K Watt Flowerbed of Bass.” See flyers from the Midwest Rave Scene collected at http://www.self-titledmag.com/yann-novak-feature-needle-exchange-mix/.

(2) See, generally, Lawrence, Tim, “Love Saves the Day”, Duke University Press, 2003 at pp. 87-104.

(3) Id. My Puerto Rican and Mexican grandmother always use to tell me I am “Latin.” As a white woman of mixed ancestry who has used music to try to connect with this part of herself and family history, I have mixed feelings about the term “Latin American” because it is Eurocentric, and as such can be viewed as negating indigenous family histories. See Simón, Yara, “Hispanic vs. Latino vs. Latinx: A Brief History of How These Words Originated”.

(4) Lawrence at pp. 199-124.

(5) See Roland advisement featuring keyboardist Oscar Peterson.

(6) See Propellerhead’s Interview with DJ Pierre.

(7) Eliade, Mircea, “Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy,” 1964, citing the 1992 Princeton University Press edition at 168. An important note regarding Eliade’s terminology: starting in the 20th century with anthropologists like Eliade, the use of the word Shamanism as a way to describe a diasporic set of ecstatic practices around the world is appropriative because the word Shamanism belongs to the indigenous people of Siberia. Accordingly, I try to use commonly used adjectives and verbs from English (ecstatic, trance, magic, drone) as much as possible when describing ecstatic healing practices as a set of tools found around the world.

(8) Id.

(9) Henderson, Katie, “Shamanic Drumming”.

(10) See Pengelley, Heather, “What’s the Science Behind Shamanism”, July 9, 2020 (collecting and summarizing available research).

(11) See “The Science of Brainwaves, the Language of the Brain”.

(12) As a child this imagery filled me with a sense of wonder, as an adult I recognize that the costumes used do not accurately reflect the human timeline.

(13) Mandela is the Sanskrit word for “Circle.” “In various spiritual traditions, mandalas may be employed for focusing attention of practitioners and adepts, as a spiritual guidance tool, for establishing a sacred space and as an aid to meditation and trance induction. In the Eastern religions of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Shintoism it is used as a map representing deities, or specially in the case of Shintoism, paradises, kami or actual shrines.” Quoting Mandala. I have not found a word in English which describes what I see in a trance state, so I use the term Mandala illustratively here. I do not intend to imply that my experience as a Raver is an alternate path to the realities accessed by these religions. There may in fact be some connection but it would be naïve and appropriative for me to assume the content of the experience is the same.

(14) “Gnosis” is the Greek word for “knowledge.” It used in the context of understanding spiritual mysteries.

(15) “The average song length on the Billboard Hot 100 has decreased by 20 seconds in the past five years. Songs now average 3 minutes and 30 seconds.” Sanchez, Daniel “Pop Songs Have Become Significantly Shorter Over the Past 5 Years”, January 18, 2019.

(16) Oliveros, Dempster, Paniotis, “Deep Listening”, New Albion, 1989, see . See also here.

(17) See https://news.rpi.edu/content/2016/11/30/remembering-deep-listener-pioneer-pauline-oliveros.

(18) The typical party is very hot. I call the wetness that drips from the ceiling “Rave Rain.” A raver need not dance to sweat. The development of so-called “Magical Heat” is technique in many spiritual practices. See, generally, Eliade at 474-475. Dance music samples and memes are replete with reference to internal heat. See, e.g., Rhythm Section’s 1992 Hardcore anthem “Burnin’ Up”.

(19) For example, during a traditional Ayahuasca ceremony, the healer plays a rattle (which serves the same purposes as the drum) and moves about the circle, however participants often remain seated or otherwise stationary during the ritual. The participants focus on the sound, visuals and song of the Icaro, but do not necessarily move or dance.

(20) See, e.g., Eliade, p. 217, discussing traditions among the Tatars and Buryat.

(21) Eliade, p. 223.

(22) Compare these substances to the psychedelic Ayahuasca, which is an indigenous technology. Healers train for years to properly prepare the Ayahuasca brew from plants. I have never seen an Ayahuasca preparation at a Rave.

(23) Barker, Stephen A., “N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), an Endogenous Hallucinogen: Past, Present, and Future Research to Determine Its Role and Function”.

(24) See Eliade, pp. 220, 223, 228, 278, for examples of cultures which use mushrooms in ecstatic rituals.

(25) See the MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Research) website.

(26) “Set and setting” is psychedelic terminology which acknowledges that a user’s environment (“setting”) and current state of psyche (mind-“set”) have a tremendous impact on the content of the psychedelic experience.

(27) See, e.g., the previously cited interview with DJ Pierre.

(28) Available here.

(29) See “MDMA (Ecstasy) Abuse Research Report”.

(30) The legislative, executive, and judicial response was to vilify the Raves and make it very hard and extra dangerous for Ravers to conduct their rituals. For example, the Chicago Rave Ordinance made it illegal for parties to go past 2 a.m. without a highly restrictive Public Place of Amusement license. The Ordinance allows fines of up to $10,000 for promoters, venue owners, AND the DJs. See Obejas, Achy and Townsend, Audarshira, “Raves Rock On, Laws or Not,” Chicago Tribune, May 22, 2000.

(31) See August 26, 2017 MAPS Press Release.

(32) Tony Wilson, “24 Hour Party People” FAC424 (2002).

(33) Production House (1992). Nino is the production alias of Terry “Juice” Jones, one of UK Hardcore’s most transcendent and amazing artists.

(34) Communique (1994), available here.

(35) For example, Cocaethylene (CE) is a toxic and dangerous metabolite that is formed after simultaneous consumption of cocaine and ethanol. See article titled “Patients with detectable cocaethylene are more likely to require intensive care unit admission after trauma”, Sept. 18, 2009.

(36) A thanks to my dear friends over the years who I played with during private sessions!

(37) Eliade, at p. 147.

(38) Eliade, at p. 168.

(39) See, e.g., Elide at p. 125 n. 36, p. 258 (collecting examples from the Chuckchee, Kamchadal, Asiatic Eskimo, Korak, manang bali of the Sea Dyak, Patagonians, Araucanians, Araphaho, Cheyene, Ute).

(40) Id.

(41) See, e.g., Eliade at 351, discussing the “mockery” of shaman who dress and live the lifestyle of a woman outside of the ceremonial context.

(42) Eliade, at p. 258.

(43) Eliade, at p. 255.

(44) EMD, “Sonic Rorschach: Dance Music as Collage and Its Dancing Subjectivities”.

(45) See, generally, Glossolalia.

(46) Mr. Fingers, “Can U Feel It? (Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Mix)”, Trax Records.

(47) See Who Sampled entry here.

About the Author

Eris Drew is a DJ, producer and trans ecstatic from the prairies of Illinois, USA. She runs the T4T LUV NRG recording label with her loving b2b partner Octo Octa. Eris is also a recording artist for Naive Records out of Portugal and conducts the Psychedelic Rites of the Motherbeat at various locations, including Pittsburgh’s Hot Mass, TUF in Seattle, and Room 4 Resistance in Berlin. Eris has been playing and programming keyboards since she was a child. A long-time resident at Chicago’s Smart Bar and DJ for the Bunker NY, she starting mixing records in 1994 at the age of 18. Her experiences as a musician and dancer showed her that rave is a powerful apparatus which can be used to transform individual lives and communities.

Follow Eris on SoundCloud, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter.

Wonderful article. Sitting at home during this pandemic and deeply missing the rave release had me reflecting: “what exactly is it that I miss so much?”, and you gave me all the answers. Thank you, Eris <3