Spring in the Fall

Brooklyn is blooming. My neighborhood is alive once more. Our sidewalks froze over, the cars wore snow tires, the windows got icy, and we simply stopped.

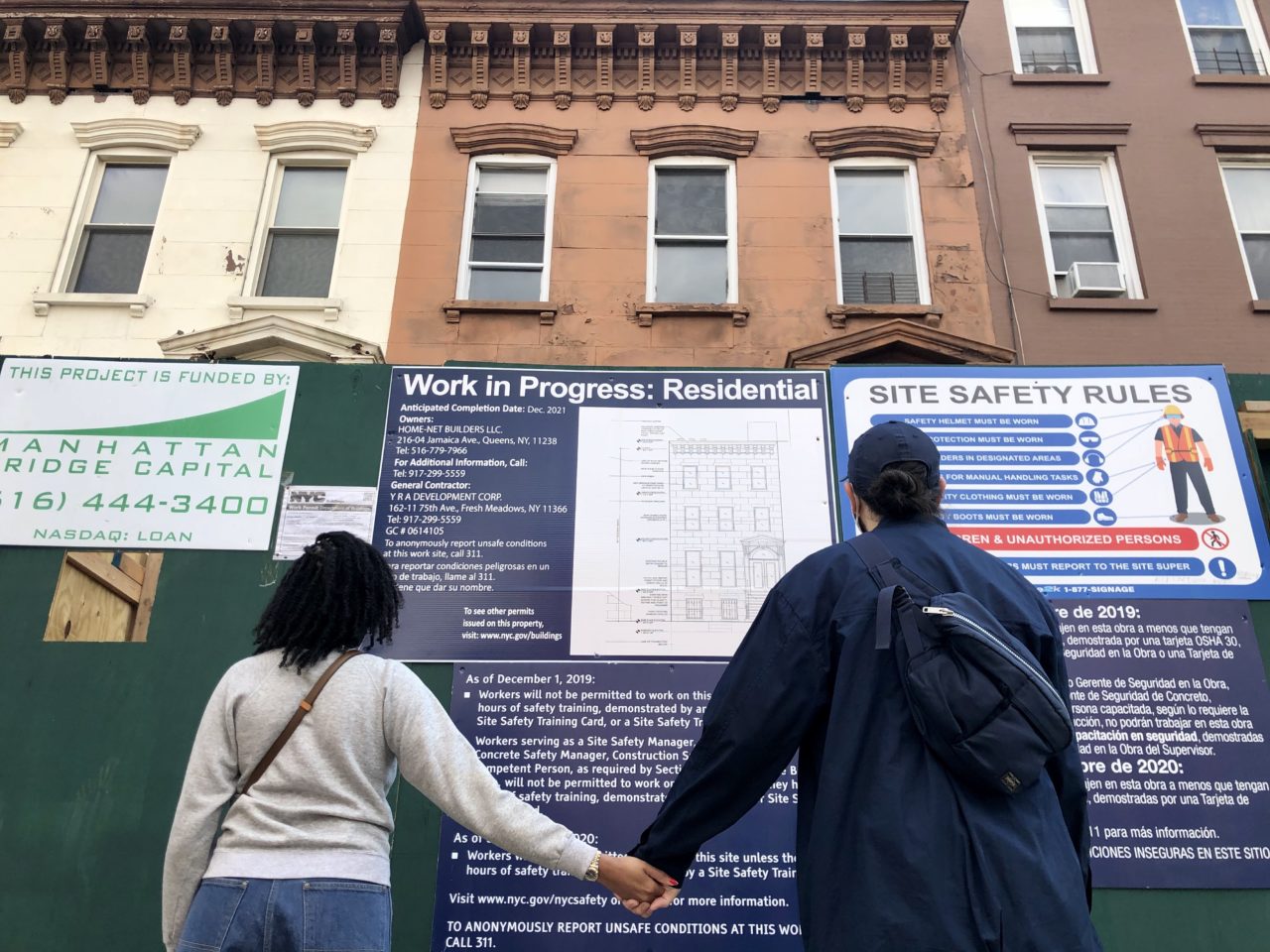

Frozen in time. Here and there, now, tiny buds are sprouting… a face here, a face there, air hugs and tender eye smiles…. We are alive. Strolling through the long blocks lined with trees facing gated stoops, I marvel at what has become….

Brooklyn, I missed you.

I told someone they looked good today, they were enjoying drinks with their friends and I got to see their face as they smiled and jokingly said “I like you,” with that particularly pleasant tone…. I saw a friend today, we hugged from the side, faces turned away from one another, but we hugged…. I watched my sister play tag with children we know not in the park today… joyful screams and all, kids filling their lungs with air, unbothered by the filter in their way, jump, tap, run, live…. Finally, they can.

The fog is lifting. The grayish, old-timey, brown-like Instagram filter is fading. I remember the time when each email started with “hope all is well with you during these unprecedented times,” the time in which all we could talk about was just that: these unprecedented times. Times have changed. Things will probably never be the same but that is no longer the end of the world. My mother would always say, amongst other things, “c’est pas la fin du monde, parce que la fin du monde c’est la fin du monde” (it’s not the end of the world, because the end of the world is the end on the world). She was right then and she is right now.

I cannot say for sure if being confined and facing a pandemic will change how we see one another or how we interact, but I believe it is safe to say we are a little less oblivious, a little less like the stereotypical trust fund kid that takes everything for granted. You know those dystopian shows where adults suddenly disappear leaving children to fend for themselves and build new societies? Yeah, kind of like that, Mother Nature wiped us from the streets. “You are my children,” she said, “and I’m sick of your ridiculously large egos,” she grinned: “that’s it, you’re all grounded,” she imposed, putting her foot down.

To her, we are a collective. To us, we are all other, separate, distinct. Way before any sort of physical danger from a stranger’s proximity, we feared our fellow humans. I didn’t realize the extent to which this is true until living on my block, a neighbourly one. Here, we chat, catch up, jokingly tease one another, check-in, like a little village. In Manhattan, I used to avoid everything from eye contact to a helpful hand. Brooklyn is like this little magical space between city living and suburbia. You get the house and the neighbours, but you’re never far enough that you lose your New Yorker title. As I hop down my stoop, open the gate, mindlessly stroll to the deli, I am still home.

Recently, I did so, completely forgetting masks were a thing and not just a fashion statement. As I neared the deli, to my right, I noticed humans and was promptly interrupted by my “oh no, I forgot my mask” realization. Wide-eyed, I looked to the humans, who met my startling confusion with laughter and reassuring phrases like “same man, I totally get it.” Kindly, one of them went inside to get a pack of surgical blue masks. I pulled one out, minding not to touch any others, thanked her, carried on, and waved goodbye as I passed them again, carrying a smiling “have a nice day” plastic bag.

That moment felt so casual, so habitual, like forgetting an umbrella when it rains, and so I wonder… how did we get from “these unprecedented times” to “this is normal?” I know not just as much as I know for a fact that wearing a mask to go to the deli and making it a point to enjoy my friends’ company outdoors is my norm.

Not unlike grief, we went through our phases starting with the initial denial marked with a mix of frazzled “this can’t be happening”s and relaxed “no worries, this is just like the swine flu”s. We went on to anger. In the US, such rage manifested itself in anti-covid or anti-government-control or anti-I-don’t-know-what protests: people filling the streets, standing shoulder to shoulder, screaming and yelling about their freedom of speech. We bargained with the classic “what if I wear my mask over my mouth but not my nose, just so I can breathe better” suggestion. Finally, here we are. Acceptance.

My mother died last year. She died. I say “died” because “passed away” is a lie… death, loss, grief, is permanent. Nested in confinement, my family was blessed with a cocoon in which to sink into. Tight-knit like those woven trees, struck by machetes, our sap drained, our bark started to peel… Somehow our guardian gardener imposed themselves, trimming, grooming, loving, hoping… they turned our tears to rain and pain to warmth in a healing caress. Our tree is healing now, growing, intertwining itself further, deeper, differently.

There is pain in feeling better. Pain in doing better. Should I leave myself shattered longer? Do I have the right to put myself back together? Does my happiness take away from my broken soul? These are the questions of a grieving daughter. “Maman, is it okay for me to be okay?” If she could, she’d say that’s all she’s ever wished for. When someone dies, everyone, and I do mean everyone, will tell you, “they’re still with you.” The thought is swallowed like one of those bitter sweet-coated pills that sat too long and now tastes of the compacted chemicals intended to ease your aching head. Irritated, I’d tell myself they can’t get it and they can’t, but they aren’t all that wrong despite being cheesy as hell. Brooklyn did the same with all its bargaining, “it’s not fair,” we’d say, “I just want to live my life,” we’d complain in the ears of those who’d say, “it’s not permanent, just breathe.” They were right, not being able to go into shops or invite someone out for a drink wasn’t permanent, but the world has changed. For the better? I have no clue, but it certainly hasn’t changed for the worst.

The fog is lifting.

My mother died, and yet I am okay. We don’t and won’t “move on,” but we move forward…. She used to be a constant presence on my shoulder, keeping me a poke away from collapsing into deep, deep grief. She now resides right behind me, presiding over my journey to happy. I cry tears of joy at the thought of her pride.

Brooklyn, you disappeared. I thought I had lost you, but you were just hibernating. Welcome back, welcome home. Brooklynites, you are here and I smile. Loud cackles and hand-holding hover around me as I march to Walgreens… blasting music in my ears and nodding at the African-patterned-masks-vendor on the corner, I am at ease in my neighbourhood once again. This is spring in the fall.

About the Author

Iman M’Fah-Traoré is a French New Yorker. Originally born in Paris, she moved to New York in her young years and majored in Politics and Governance at Ryerson University, Toronto. She is now attending the New School in NYC for Global Studies. The Ivorian and Brazilian writer works with The Womanity Project, a non-profit that challenges gender equity with innovative workshops. Currently, she is working towards assembling her first poetry book. Her writing specializes in LGBTQ+, grief and trauma, and race and ethnicity poetry and essays.

View Comments

No Comments (Hide)