Beyond Borders: An Interview with Anika Ahuja & Sara Graorac

Artists Anika Ahuja and Sara Graorac gracefully unpack for us the themes of their powerfully moving installation. Through heavy anecdotal references from their respective upbringings, we are given a glimpse at some of the decision making behind the piece and the overall critiques it provides. “(Something) with a decorative edge.” is on display in our vitrine until September 23rd.

First of all: “(Something) with a decorative edge.”— give us a bit of insight as to why you two chose this title.

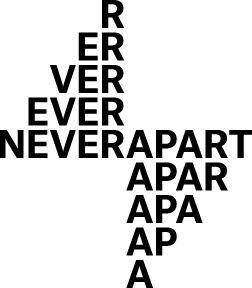

SARA: It’s been over a year since we began the dialogue and process surrounding this project. I feel like we both struggled with a title until the last minute. We even considered pushing the travel agency/logo element, but finally agreed on the ornamental definition of a border — a play on words.

ANIKA: I think we decided that boundaries and borders, both perceived and literal, were a big part of what we wanted to talk about with this project, considering that both of our family backgrounds are from places that no longer exist (former Yugoslavia for Sara, and the northern part of Punjab, India that is now Pakistan for myself). And in considering how cultural elements, and identities are often reduced to mostly decorative or ornamental, (think cultural dress, jewelry, colours, flags), the title became that. The literal definition of a decorative border.

Can you talk a little about the themes involved in the piece and how your own personal experiences aided in its development ?

SARA: For me, themes range from my connection to Balkan aesthetics and folklore, as well as the interesting overlap we find between different cultural backgrounds (especially mine and Anika’s), to borderities and mass communication. My personal experience of being a first-generation child refugee impacts my research and process. When my family fled former Yugoslavia, I was too young to be very aware of reality. That’s why my creative process is heavily based on storytelling and listening to my relatives. I want to continue exploring the concept of being from a place that no longer exists.

ANIKA: We talked a lot about cross cultural identities, and what it means to occupy space as a third-culture person. As an Indo-Canadian, and Canadian born citizen, it has always been a struggle to identify which parts of myself were distinctly Canadian, or distinctly Indian. Having lived in both countries, and feeling relatively out of place in both, I guess this project has been an exploration in identifying cultural ownership. By recreating traditional elements in unconventional materials, I’ve been trying to consider what we have rights to, what constitutes cultural appropriation, and what we feel an inherent sense of connection with.

Can you speak a bit more specifically on how this installation pertains to identity politics and the ways it speaks to or raises concerns of cultural homogenization ?

SARA: I don’t claim identity politics as part of my practice, especially considering I’m clearly a white, cisgendered and able-bodied woman. I’m not always read and stereotyped as such — if anything, I profit off identity politics — and it’s important for me to be aware of that. Especially since aesthetics (and by extension, art) are political, it wouldn’t be appropriate for me to personally discuss identity politics as a tool. I think with this project we are more interested in opening interpretation of the merging of two distinct cultures. We wanted to visualize the absurd, manufactured concept of borders, from small- to large-scale.

ANIKA: This project was so deeply personal for both of us, that I’m not sure that the intention really is to raise concerns about cultural homogenization, so much as highlight the complexities of “western” identity. All the elements of this piece relate directly to our personal experiences, and it’s important to note that we are not trying to speak for anyone else. In my experience, having an Indian background came with a lot of shame and was something I would readily repress about myself so as to not be othered when I was younger. So reclaiming elements of that background has been a really challenging and slow, but incredibly rewarding process. I’m far more interested in my Canadian and Indian identities existing in harmony with one another than I ever thought I would be. I think what is difficult is, to see those elements of my Indian heritage being consumed by the society that initially made me feel shame for those things. That’s the conflict. And quite frankly I’m not entirely sure of the solution, but of course highlighting the consumerist culture of the west is part of the conversation here. It’s about the border between consideration and consumption.

We talked a bit about these “cultural silos” that Westerners tend to create— or the “Western gaze” so to speak. How can your piece be interpreted as a critique of how the West claims ownership of, or “colonizes” aspects of non-Western culture ?

SARA: Interesting question. I’m going to let Anika unpack this since it doesn’t pertain much to white immigrants.

ANIKA: A big intention is to discuss the contradictions often occurring between dialogue about travel, and conversations concerning refugees and migrants. Travelling east is most often conveyed superficially and exploitatively by means of social media and advertising: “an exploration of silk”, “a culinary adventure!”, “Visit a beach!”, “Ride an elephant!”, and there is this massive disconnect, since these places are often in or adjacent to areas of political strife, or environmental crises. And it’s really easy to visit a place and disconnect from it being a country of real human people with goals and aspirations, and complicated socio-political histories and backgrounds. Then living in a city like Montreal, that is by and large a “multicultural” city, but that immigrants and refugees still often only occupy select neighbourhoods and communities. I can’t truly say that the installation is a critique so much as a consideration of what it means to be able to cross borders and still have a home. To have the privilege of travel without sacrificing your cultural identity, and simultaneously being able to consume and enjoy other cultures that are available to you. Meanwhile, immigrants and refugees, who are often escaping situations of conflict, or searching for better opportunities for themselves and their families, still mostly exist within ‘borders’ in our Western cities. And what does that mean? The truth is we are all guilty of not delving beyond the surface, of going to Chinatown and Little India when we’re craving spicy food without considering the people who built and nourished these cultural safe-spaces for themselves. Not to mention property investment and gentrification taking over these spaces. With this installation I am encouraging viewers to ask questions, and to look a bit harder. Not everything you have access to is yours to take.

How do you want people to navigate the installation ? What is it your hope that audiences glean from what’s contained inside ?

SARA: This project was completely dependent on the space, and when Never Apart approached us it really came together. The vitrine is like its own little store within a space. It’s perfect. That’s the vibe we wanted — a bubble that was physically inaccessible, though hyper-accessible in a visual sense (consider those dilapidated, sun-bleached storefronts we pass by every day). I hope this creates a new dynamic between artwork and audience, and encourages people to look, read a little for clues, then look again. By moving along the window, we notice new elements that may have been obscured from our previous viewpoint, and it’s frustrating at the same time because many of us are tactile and want to interact with it.

The images on the back wall are taken by Anika and I on our respective travels to Delhi and Montenegro. These images represent our (now foreign) gaze upon our return “home”. I’ve been collecting cell phone images from every trip back, and I eventually want to make a project out of them. It feels like a surreal, broken telephone, like I am fetishizing my own birthplace by photographing things that seem inane — the process is never too sentimental or taken too seriously.

The glass heart is a focal point, as it’s well-lit and not totally obscured. The text used in the heart is from a research paper about postwar tourism strategies in Croatia. The engraved excerpt I chose (“samo ti [only you] . . . stable, desirable and legitimate”) are descriptions used in order to seduce Northern Europeans and Westerners. It was and still is an attempt to stimulate the economy, as tourism to the Balkans dropped significantly in the 1990s. The most remarkable part is that there is a complete omission of any indication of the civil war in these travel brochures. It’s quite dark — they chose a method of “covering up” rather than accountability, which could promote ultimate healing. And once you’re in former Yugoslavia, there’s no fooling anyone — there are still bullet holes and destroyed properties in the middle of some cities. The war is part of the cultural fabric as it remains imprinted in recent memory.

ANIKA: It’s always really important to me that the viewer create their own understanding of the work. We were very intentional in making the piece difficult to read and access. With the intention of discussing borders, it was important to create a border between the viewer and the work. In obscuring the glass, as Sara mentioned, we ask the audience the look beyond the surface. Ideally the audience thinks, “what is that? What does it mean? Why is it here? I want to know more”. But if they only come to “I don’t get this, that thing is pretty, or interesting” that is also enough, because it’s a reflection of how we perceive these experiences and references in real life, and that is the honest truth for a lot of people. In making reference to storefronts and window displays, we are making a direct reference to those businesses and places of commercial and cultural exchange that are so often owned or employed by members of marginal/immigrant communities, we would hope that the audience would naturally make that connection themselves.

There are “calling cards” in one of the display cases that may be one of the most overlooked or difficult to read elements of the installation. Sara and I used our own images from family and travels to fabricate these faux international calling cards to mimic to the ones available at corner stores and depanneurs, familiar to immigrant communities who use cheap third-party phone services to contact their family, and community members abroad. The cards reference an access point to a line of communication that exists across borders. Though yet again, these access points (cards) are inaccessible to the viewers in the gallery who are unable to breach the border of the vitrine. Everything, every single thing in the installation is intentional. Everything is there for a reason, from the blinds on the wall, to the specific images that have been hand printed onto the carpet. We know why they are there and what they mean to us, but I also am happy to allow the viewers to create their own narrative and to hopefully question and counter their perceptions.

View Comments

No Comments (Hide)