In Spirit: Akhara Pulse

The Akhara is a space designated for Indian wrestling. It is a large and open yet protected area with a water well, trees, and clean ground where the indian wrestling takes place.

In ancient times, the wrestlers, kusthi, were seen as ascetic, as their lives were regulate by very specific rules — food, sleep, sexualityl, and training of course, were decided by the master. Nowadays, the obligations of modern life do not allow the wrestlers to keep this ascetic discipline, however akharas still exist in northern India and it is up to the wrestlers to decide until which point they bring the antiquated wrestling way of living into their own life. The practice revolves around the devotion to the lord Hanuman. No practice can begin, no weights can be used, before worshiping the monkey God. In October 2016, I investigated these akharas, and more specifically, I spent one week within the Tulsi Das Akhara of Varanasi.

L’Akhara est le nom donné à l’espace où se pratique la lutte indienne. Il est large et protégé, avec un puits, des arbres et un sol propre.

Dans les temps anciens, les lutteurs, kusthi, étaient tel des ascètes dont la vie était régulée par des règles très précises — nourriture, sommeil, sexualité, et l’entraînement bien entendu, étaient décidés par le maître. De nos jours, les obligations de la vie moderne ne permettent plus aux lutteurs de fonctionner avec un modèle de discipline ascétique. Les akharas existent toujours dans le nord de l’Inde et les lutteurs décident jusqu’à quel point ils intègrent certains principes du kushti dans leur vie quotidienne. La pratique s’organise autours de la dévotion du Dieu Hanuman. Aucune pratique ne peut débuter, ou un poids soulevé, sans une marque de dévotion au dieu Singe. Durant le mois d’octobre 2016, je me suis immergée dans l’univers de ces akharas, et plus spécifiquement, j’ai passé une semaine au sein du Tulsi Das Akhara de Bénarès.

The center of the akhara is the shrine dedicated to Lord Hanuman, the monkey God, carrying a club, called gada. No akhara can exists without a shrine. The shrine is placed in a square architecture covered with a roof supported by pillars only, delimited by borders made of dry mud which represents the space where the wrestlers fight. Around this wrestling pit is an open area where the wrestler can do their physical training. Weights, parallel bars, and gadas are all around and are for anyone to use. The tools are usually painted red or orange — the colours of the God.

The gada training is among the most important part when it comes to the specificity of Indian wrestling. I was able to observe two kinds of gadas: large clubs and an enormous weight mounted on one end of a bamboo stick. The weights vary from 20 to 60 kilograms. The video depicts how they are manipulated. Even though I tried many times, the weights were too heavy for me and I prefered to work with a smaller log with carved handles that I would lift from in between my legs, around my neck, and from one side to the other. The weight training is the first step of the wrestlers’ lives, allowing them to gain strength and ability. With the gadas, the body develops according to the movements needed for the wrestler. These should be performed daily. The second stage of the training is — like in any traditional art — observation, when the students must watch the elder before getting into the arena. Finally, when he is ready, the wrestler will start training his wrestling techniques in the wrestling pit and measure his strength with other kushti.

Au coeur de l’akhara se trouve le sanctuaire dédié à Hanuman, le dieu Singe, qui porte une massue appelée gada. Aucun akhara ne peut exister sans un templion. Celui-ci est placé dans une structure ouverte de forme carrée dont l’espace est délimité par une bordure de boue sèche avec un toit soutenu par des pylônes, où les kusthi pratiquent la lutte. Autour du terrain de lutte, un espace ouvert où les lutteurs peuvent s’adonner à leur entraînement physique. Poids, barres parallèles et gadas sont disponibles et prêts à être utilisés par les pratiquants. Les instruments sont généralement peints en orange ou rouge, couleurs de la déité.

L’entraînement des gadas est l’une des parties les plus importantes et spécifiques à la lutte indienne. J’ai pu observer deux sortes de gadas : de larges massues, et un poids monté sur un bâton de bambou. Les poids peuvent varier de 20 à 60kg. Les vidéos montrent comment est-ce que les poids sont manipulés. Même si j’ai essayé plusieurs fois, ceux-ci étaient trop lourd pour moi alors je préfèrais m’entrainer avec une petite bûche munie de poignées creusées à l’intérieur du rondin que je devais saisir entre mes jambe, faire passer derrière ma nuque, ainsi de suite d’un côté puis l’autre. L’entraînement des poids est la première étape de la vie des lutteurs et doit idéalement se pratiquer tous les jours. La deuxième étape de l’entraînement est, comme dans tout art traditionnel, l’observation. L’étudiant regarde les aînés avant de conquérir à son tour l’arène de lutte. Finalement, lorsqu’il est prêt, le lutteur commencera à s’entraîner aux techniques de lutte dans l’espace réservé à la pratique, pour mesurer sa force avec celle des autres lutteurs.

Wrestlers are typically young, between 17 and 35 years old. The older wrestlers still come to the akhara to teach the younger or just enjoy a bit of movement and the atmosphere of the place. In their daily lives, wrestlers may work at the train station, as boatmen, milk makers, cooks, cleaners, and sometimes even students. Women are not permitted. When I asked if I could try, I was surprised that the master of the place allowed me to do the physical training with the others, but I could not step into the wrestling pit which is sacred and reserved for men only.

Les lutteurs sont généralement jeunes, entre 17 et 35ans. Les plus vieux continuent de venir à l’akhara pour enseigner aux plus jeunes ou encore pour le simple plaisir de bouger un peu et de profiter de l’atmosphère du lieu. Dans leur vie quotidienne, les lutteurs travaillent à la station de train, ils sont “boatmen”, “milk maker”, cuisiniers, hommes de ménage, et parfois étudiants. Les femmes sont interdites. Lorsque j’ai demandé si je pouvais essayer, je fus surprise lorsque le maître m’ouvrit l’espace de l’entraînement physique avec les autres kushti, en spécifiant tout de même que je ne pourrai pas rentrer sur l’arène de lutte, espace sacrée réservé aux hommes.

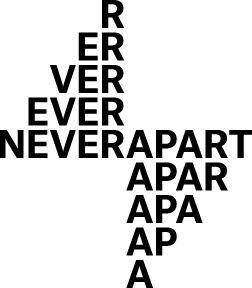

The more one moves towards the center, the closer he gets to the God. Wrestling is not about personal strength, rather it is about embodying the God’s power. The physical training made in the periphery of the akhara helps strengthening the body. When the body is ready, the teaching of the wrestling techniques starts. The soil found in the wrestling pit is highly symbolic. It is always cleaned, hydrated and offerings of flowers and incense are made before starting the practice each day. At the end of the practice, the soil covering the kusthi’s bodies, mixed with their sweat, becomes clay. Through the practice, the wrestlers transformed from human beings into clay Gods resembling the deities’ statues worshipped in hinduism. For Indians, the body’s leftovers, such as sweat, nails, or hair, are considered impure, especially when it comes from a lower cast. In the akhara they are transformed: humans leave their limited nature to become empowered by the God, this is how all casts can practice together. Like it is found in some very ancient tribal rituals such as theyyam, the social boundaries are surpassed and the lower becomes the higher, when infused with the energy of the God.

As Dr. Joseph Alter writes in his study about Indian wrestling, Hanuman is not a metaphysical god. The akhara represents the metaphysic grounded in the concrete aspects of life. The connection to the earth is the symbol of the human being grounded in life. The body gets its strength from the earth, the air, and the water, which are key elements of the akhara (soil, wind and water well) and the body (flesh, breath and sweat). An alchemy of the body operates — it becomes stronger. Not only for the mere strength itself, but stronger in its vitality. The body becomes the reflection of the essential principles of life, and therefore the basis of any metaphysical embodiment.

It is spirituality in its most grounded state, a reminder that it is first of all about life and not about metaphysical experiences. One can ascend to the mystical heavens only when deeply grounded in the earth. Dr. David Gordon White, in his study of the siddhas (also called yogis or tantrika), echos the same views: yogis are alchemist of the concrete, working with the body and its substance, from the overt to the subtle, as a mere continuity of the form. He insists that Indian metaphysics is first of any concrete matter.

Plus on se déplace vers le centre, plus on se rapproche de Dieu. La lutte ne concerne pas la force personnelle, il s’agit d’incarner la force du Dieu. L’entraînement physique qui s’exécute dans la périphérie de l’akhara permet de renforcer le corps. Quand le corps est prêt, l’enseignement des techniques de lutte commence. La terre que l’on trouve dans l’arène est hautement symbolique. Elle est constamment nettoyée, hydratée et des offrandes de fleurs et d’encens lui sont faites avant de débuter la pratique chaque jour. À la fin de la pratique, la terre qui couvre le corps des lutteurs mélangée à leur sueur est transformée en boue. À travers la pratique, le kushti se transforme en déité de terre comme celles que l’on idolâtre dans l’hindouisme. Pour les indiens, les déchets du corps tels que la sueur, les ongles ou les cheveux sont impurs, surtout lorsqu’ils proviennent d’une caste plus basse. Dans l’akhara pourtant, le corps est transformé: l’humain quitte sa nature limitée pour incarner le dieu, c’est ainsi toutes les castes peuvent pratiques ensemble. Tout comme on le prouve dans certains rituels tribaux comme le theyyam, les barrières sociales sont dépassées et le plus bas devient le plus haut, lorsqu’il est infusé par l’énergie du dieu.

Comme le Dr. Joseph Alter l’écrit dans son étude sur la lutte indienne, Hanuman n’est pas un dieu métaphysique. L’akhara représente la métaphysique ancrée dans ses aspects concrets de la vie. La connexion avec la terre est le symbole de l’être humain ancré dans la vie. Le corps prend sa force de la terre, de l’air et de l’eau, qui sont les éléments clés de l’akhara (terre, vent et eau du puit) et du corps (chaire, respiration et sueur). L’alchimie du corps peut s’opérer; il devient plus fort. Pas seulement pour la force elle-même, mais plus fort dans sa vitalité. Le corps devient la réflection des principes de la vie, à la base de tout incarnation métaphysique.

C’est là la spiritualité dans sa forme la plus enracinée, un rappel qu’elle est avant tout à propos de la vie et non à propos des expériences métaphysiques. Chacun peut accéder aux cieux mystiques seulement lorsqu’il s’est enraciné dans le sol. Dr David Gordon White, dans son étude sur les siddhas (aussi appelé yogis ou tantrikas) fait écho à cette perspective: les yogis sont les alchimistes du concret, travaillant avec le corps et sa substance, de la matière au subtil, comme simple continuité de la forme. Il insiste sur le fait que la métaphysique indienne est avant tout une affaire du concret.

Each morning is adjoined by the same routine, except for wednesday when there is no wrestling but of taking care of the body and the akhara itself: wetting the soil, watering the trees, oiling the body, massaging and chatting. On regular mornings, the wrestlers should arrive in the akhara with a clean body, empty bowel and good mind-set, ready to practice. In the early morning, around 6:30am, the place is cleaned up of fallen tree leaves, the hearth of the arena ground is turned over, white flowers are picked from the bushes and thrown onto it as a sign of devotion for the space of practice. The Hanuman temple is prepared for worship: flowers are offered, Ganga water, as well as sweets or bananas that will become the prasad, or the food from the Gods given to the wrestlers at the end of the practice. At 7:30am, the wrestler salute the God and the practice can start. Physical training to make the muscles stronger and the movements with the gadas are done around the arena. The most important body parts of the kushti are his thighs and shoulders. During the fighting practice, they face each other, bending with their arms lifted up. Regularly they hit their thighs in a curt manner symbolic of their strength, a gesture resembling polynesian warriors. The master is always around, correcting his students, showing new techniques. He looks at each kusthti and helps them with very precise movements and explanations. He has the reputation to be one of the best guru of the city.

Chaque matin se déroule suivant la même routine, à l’exception des mercredis où il n’y a pas d’entraînement mais le soin du corps et de l’akhara lui-même: hydrater le sol, arroser les arbres, huiler le corps, se masser et discuter. Le reste des matinées, les lutteurs doivent arriver à l’akhara le corps propre, les intestins vides et dans un bon état d’esprit, prêts à pratiquer. Tôt dans la matinée, vers 6h30, les feuilles tombées au sol sont ramassées, la terre de l’arena est retournée, des fleurs blanches sont cueillies sur les buissons et y sont jetées comme signe de dévotion pour l’espace de pratique. Le temple d’Hanuman est préparé pour le rituel: des fleurs en offrande, de l’eau du Gange, ainsi que des “sweets” ou des bananes, qui deviendront le prasad, la nourriture des dieux qui sera offerte aux lutteurs à la fin de la pratique. À 7h30, les lutteurs saluent la déité et la pratique peut alors débuter. L’entraînement physique permet de rendre les muscles plus forts et les mouvements avec les gadas sont fait autour de l’arène. Les parties du corps les plus importantes des lutteurs sont ses cuisses et ses épaules. Pendant la pratique du combat, ils se font face, le buste incliné vers l’avant et les bras levés. Régulièrement ils frappent leurs cuisses d’un geste sec qui symbolise la force, un mouvement qui rappelle celui des guerriers polynésiens. Le maître est toujours dans les parages, corrigeant ses élèves, leur montrant de nouvelles techniques. Il observe les kushti et les aide avec des mouvements et des explications précises. Il a la réputation d’être l’un des guru les plus qualifiés de la ville.

By 9:00am, the practice ends. Kushtis talk, hang around, massage each other and stretch. Sometimes they do Kapalabati, pranyamas or some asanas — yogic practices. Finally, the wrestlers covered with mud from their training are ready to shower. They head toward the holy Ganga River. On the last day of my visit, they invited me to follow them to take photos. I was so enthusiastic, took my camera, and followed them to the Ganges. They jumped from the high walls and lathered each others backs with soap in the glistening water reflecting the rising sun. After their shower, they are ready to go to work. One of them gestures a sign to follow him as he utters “mandir”, which means “temple” in hindi, as if the morning ritual would only be finished after a visit to the temple. He starts climbing a flight of stairs leading to a small balcony with a huge bell and orange kumkum (powder) to put on the forehead as a sign of devotion. He keeps running through the stairs — one floor, two floors, three floors — and we end up on hthe last floor of a very tall building with blue walls and a picturesque view over the Ganga. I don’t have the time to appreciate before he’s already gone. He runs through doors and corridors and I discover temples that I had never seen before, hidden right above the Ghats. We now arrive in the street, going from one temple to another, making signs of devotion each time we cross an idol. When we pass by a lingam, we turn around it, then he pours some Ganga water from a small pot into my cupped right hand, for holy drinking. And the race starts again, until we arrive 10 minutes and 10 temples later back to the akhara. He picks up his bag and leaves for work, saying nothing. Indians have this beauty, that most of the time things happen in the moment and words are not needed. This sums up my week with the kushti.

Vers 9h00, la pratique se termine. Les kushtis parlent, traînent, se massent et s’étirent. Parfois ils font kapalabati, quelques pranayamas et des asanas (des pratiques yogiques). Finalement, les lutteurs couverts de la boue accumulée pendant l’entraînement sur le corps sont prêts à se laver. Ils se dirigent alors vers le Gange. Le dernier jour de ma visite, ils m’invitent à les suivre pour prendre des photos. Tellement enthousiaste, je pris mon appareil photos et je me suis mise en chemin à leur suite. Ils sautaient des hauteurs des murs et se savonnant le dos les uns les autres dans l’eau luisante reflétant le soleil levant. Après leur douche, ils sont prêt à rejoindre leur travail. L’un d’eux me fit signe de la suivre en disant “mandir”, ce qui signifie “temple” en hindi, comme si le rituel du matin ne serait terminé qu’après une visite au temple. Il commença à monter les escaliers menant à un petit balcon avec une énorme cloche et du kumkum (poudre) orange que l’on met sur le front en signe de dévotion. Il continua de courir à travers les escaliers. Un étage, deux étages, trois étages, et nous arrivons au dernier étage d’un haut bâtiment aux murs bleus, avec une vue picturale sur le Gange. Je n’ai pas le temps d’apprécier qu’il est déjà reparti. Il court à travers les portes et les corridors et je découvre des temples que je ne n’avaient jamais vu auparavant, cachés juste au-dessus des Ghats. Nous arrivons maintenant dans la rue, allant d’un temple à l’autre, faisant des signes de dévotion chaque fois que l’on croise une idole. Quand nous passons devant un lingam, nous en faisons le tour, puis il verse un peu d’eau du Gange qui vient d’un petit pot, dans ma main droite pour boire l’eau sacrée. Et la course reprend, jusqu’à ce que nous arrivions, 10min et 10 temples plus tard, de nouveau à l’akhara. Il prend son sac et s’en va, sans rien dire. L’Inde a cette beauté instantanée à laquelle les mots n’ont rien à ajouter. C’est là que s’achève ma semaine avec les kushti.

Special thanks to Ravikant who helped me and guided me through the practice.

View Comments

No Comments (Hide)