In Spirit: Ritual

I have returned from my voyage. Somehow, it feels more like a displacement than a return, almost as though my movements level out, where each place I will visit in the upcoming year brings its own functional neutrality: there is no voyage, rather only life which is deployed from one point to another with its meetings, reunions, and countless investigation of Reality.

Je rentre de voyage. Pourtant, c’est plus un déplacement qu’un retour, un peu comme si mes mouvements se nivellent de plus en plus, que chaque lieu que je visite dans l’année porte maintenant sa neutralité fonctionnelle: il n’y a pas de voyage, il n’y a que la vie qui se déploie d’un point à un autre avec ses rencontres, ses retrouvailles et l’investigation infinie de la Réalité.

In the car, I recount snippets of my trip to my father which anachronistically takes shape on the Parisian roads. More than simply facts, these are my reflections, my outlook, and my “notes” that I share with him. His questions help me to take a step back and formulate certain ideas. With this trip, it was the rituals that I have came to know, at each detour it was in my path: the women in the morning who dress the lingams with tilac and flowers, the men who purify themselves in the Ganga, the pilgrims who visit the Karnataka Joyti Lingam, meeting with my Indian friends, and then with Boris, a specialist on Abhinavagupta.

Dans la voiture, je raconte à mon père des bribes de mon voyage qui se dessinent de façon anachronique sur les routes de Paris. Plus que les faits, ce sont mes réflexions, mon regard et mes “notes” que je partage avec lui. Ses questions m’aident à prendre du recul et à formuler certaines idées. Ce voyage là, c’est le rituel que j’ai rencontré, à chaque détour il était sur mon chemin: les femmes le matin qui habillent les lingams de tilac et de fleurs, les hommes qui se purifient dans le Gange, les pèlerins qui visitent le Joyti Lingam du Karnataka, et la rencontre avec mes amies indiennes, puis avec Boris, l’un des spécialistes d’Abhinavagupta.

My father, who is well aware that I was not raised with any formal religious education, asks me: “but what ultimately attracts you to this practice?” Other than the festive aspects of the culture, it is the act of offering. I explain to him that in the occidental world we have lost this notion of thankfulness, humility in the face of that which surpasses us, and above all the notion of “duty”. In this modern world where “rights” predominates, the human being thinks everything is owed to him, beginning with an easy life filled with happiness. It is here he finds his greatest source of misery.

Mon père me questionne, lui qui est si bien placé pour savoir que j’ai grandi sans éducation religieuse: << mais qu’est-ce qui t’attire finalement dans cette pratique? >>. Outre l’aspect culturel festif, c’est l’acte d’offrande. Je lui explique qu’en occident, on a perdu cette notion de remerciement, d’humilité face à ce qui nous dépasse, et surtout la notion de “devoir”. Dans ce monde moderne où le “droit” prédomine, l’être humain pense que tout lui est dû, à commencer par une vie facile faite de bonheur. C’est là sa plus grande misère.

The ritual embodies a rich theme merely through its cultural foundation as it is manifested within India, but, moreover, for its internal and essential significance which touches the deep recesses of the being, beyond time and space. It is therefore this exploration which I am proposing this month, a voyage into the heart of the ritual within the Indian world, and beyond.

Le rituel est un thème riche par sa nature culturelle telle qu’elle se manifeste en Inde, mais aussi, et surtout pour sa signification interne et essentielle qui touche à l’être profond, au-delà du temps et de la géographie. C’est donc cette exploration que je propose ce mois-ci, un voyage au coeur du rituel dans le monde indien, et là où il le dépasse.

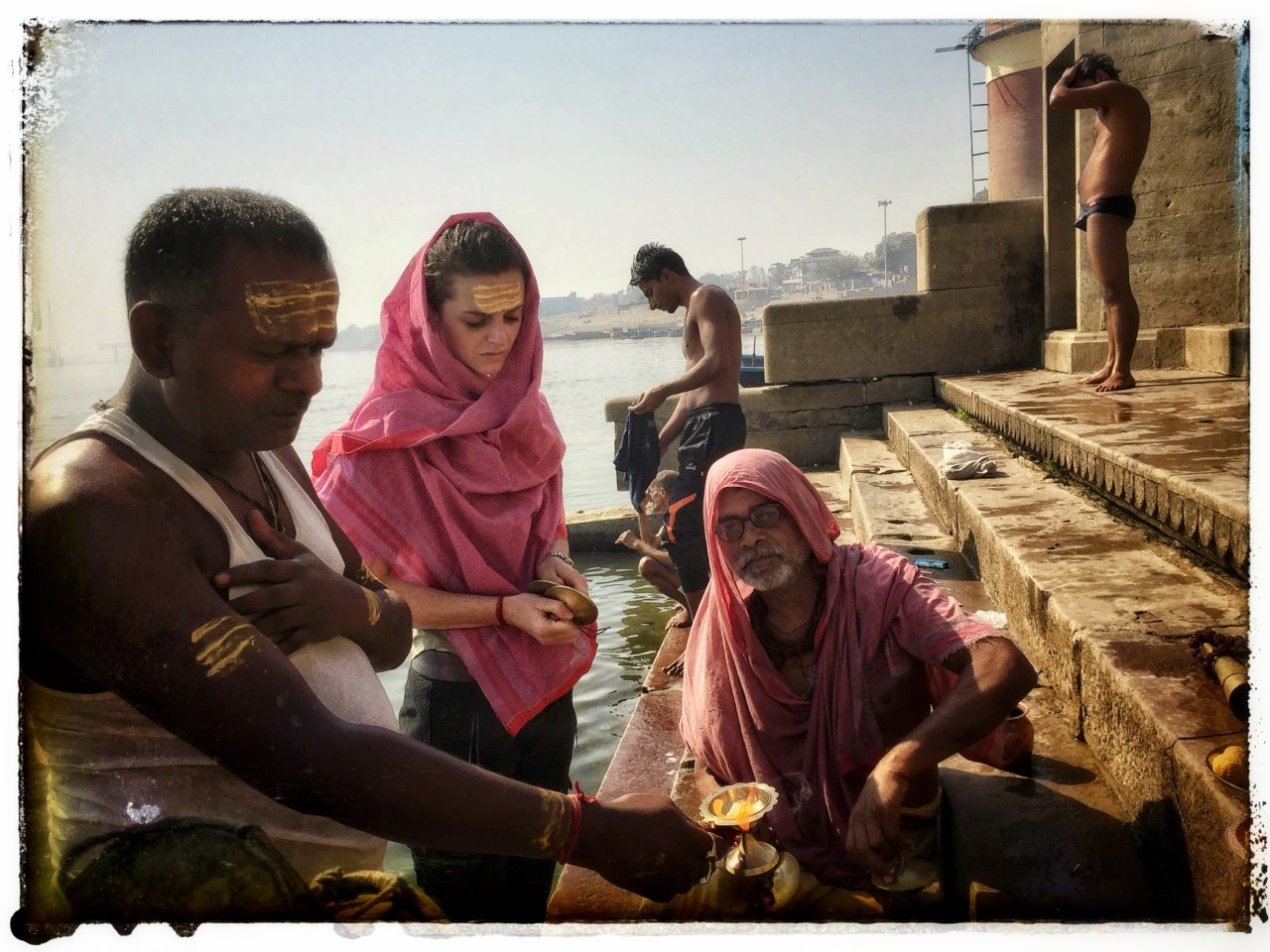

This morning, I returned to the Tulsi Ghat Akhara to greet my wrestling-friends at the end of their training. Welcomed with warm smiles and laughter, surprised to see me reappear, they invited me to share their meal, and further propose that I accompany them in the customary bathing. Upon arrival on the steps that border the Ganges, I notice a small group of mature men in the middle of their ritual. Goree, one of the wrestlers, immediately invites me to take part in the ceremony. I understand within a few minutes that the older man who speaks a few words of english is in fact his uncle, “Chacha”.

Ce matin-là, je suis retournée à l’akhara de Tulsi Ghat saluer mes amis lutteurs à la fin de leur entraînement. Accueillie avec des rires et des sourires, surpris de me voir réapparaître, ils m’invitent à partager leur nourriture, puis me proposent de les accompagner sur les ghats pour la baignade coutumière. En arrivant sur les marches qui bordent le Gange, je remarque un petit groupe d’hommes d’âge mûr en train de faire un rituel. Goree, l’un des lutteurs, m’invite tout de suite à prendre part à la petite cérémonie. Je comprends quelques minutes plus tard que le vieil homme qui parle un peu d’anglais est en fait son oncle, <<Chacha>>.

In a small group, the preparation of the ritual is not lacking in laughter and occasionally friendly quarrels. The idols, murti, are built from the clay from the Ganges. A block of dry clay is initially crumbled, mixed with some water from the Ganges and the ghee, until a perfect consistency allows for the moulding of a lingam with its yoni. Around the steps, everyone gets ready to prepare utensils for the ceremony: plates, lota (pots for pouring water from the Ganges), rice, flowers, sweets, powders, coins, and musical cymbals. The offerings are made up of typical day-to-day objects. Nothing should be missing. Uncle Chacha speaks to me insistently. Goree seems frustrated and yells at his uncle to hurry up “or else at this rate, we’ll still be at the same place by nightfall“; quickly Chacha quiets down with a timid toothless smile, only to resume the conversation with even greater fervor 5 minutes later.

En petit comité, la préparation du rituel ne manque pas de rire et parfois d’engueulades amicales. Les idoles, murti, sont construites à partir de l’argile du Gange. Un bloc de terre sèche est d’abord émietté, on y mélange alors un peu d’eau du Gange et de ghee, jusqu’à ce que la consistance parfaite permette de modeler un lingam avec son yoni. Autour des marches, tout le monde s’active pour préparer les ustensiles de la cérémonie: assiette, lota (pot pour verser l’eau du Gange), riz, fleurs, sucreries, poudres, pièce de monnaie, cymbales pour la musique. Les offrandes se composent que des produits usuels du quotidien. Rien ne doit manquer. L’oncle chacha n’arrête pas de me parler. Goree s’énerve, il lui crie de s’activer <<sinon à ce train-là, ce soir on y sera encore>>, alors chacha se tait en souriant timidement, découvrant sa bouche édentée, pour reprendre la conversation de plus belle 5 min plus tard.

On the 21st of February is the Shivaratri, the festival celebrating the matrimony of Siva and Parvarti. The ritual, therefore, takes on an entirely new scope. On this day, the ritual last must longer, up to 4 hours under the blazing sun. Countless people wish to participate, the sacred icons and the offerings are even more plentiful, and within a large cooking pot we prepare a concoction of almonds, spices, and the famous Bang, all within a milk base. On the day of the Shivaratri, everyone must eat some Bang, even children — this thin dough prepared by grinding cannabis leaves for hours on top of flat stones with almonds and cashew nuts, which makes everyone completely stoned until the next morning. The dough is consumed at the end of the ritual with the traditional liquid, performing the service of the prasad (the food of the gods) on the festive day.

Le 21 février, c’est la Shivaratri, le festival du mariage de Siva et Parvati. Le rituel prend alors une tout autre envergure. Ce jour-là, le rituel est bien plus long, il dure 4h sous un soleil de plomb. De nombreuses personnes veulent participer, les icônes et les offrandes sont en plus grand nombre, et on prépare dans une énorme marmite une substance à base de lait, d’amande, d’épices et du fameux “Bang”. Le jour de la Shivaratri, tout le monde doit manger du Bang, même les enfants, cette pâte très fine préparée en broyant pendant plusieurs heures des feuilles de cannabis sur une pierre plate avec des amandes et des noix de cajou, ce qui vaut à tout le monde d’être complètement stone jusqu’au lendemain matin. La pâte est consommée à la fin du rituel avec le liquide traditionnel, faisant office de prasad (la nourriture des dieux) en ce jour de fête.

At the end of the ritual, the lingam and the offerings are returned to the Ganges, the stones are cleaned of the orange tilac, clay, rice grains, and milk, the utensils are replaced in their rightful place in the bags, and within a matter of minutes nothing remains. One has to give up the symbolic icone, there is no sacred site, only the void and the return to nothingness — ultimate ritual.

À la fin du rituel, le lingam et ses offrandes retournent dans le Gange, on nettoie les pierres couvertes du tilac orange, de l’argile, des grains de riz et du lait, puis les ustensiles regagnent leur place dans le sac, et en quelques minutes, rien ne reste. Il n’y a aucune icône à laquelle s’attacher, aucun emplacement, seulement le vide et le retour au néant, ultime geste rituel.

In India, the mundane and religious-lives cohabitate without hierarchy and do not partake in the occidental dichotomy. For Hinduism, religion and spirituality are hardly dissociated and exist ubiquitously at all times. As one of the first woman explorers of India in the early 20th century who contributed to the enriching revelation of Indian culture said: “if you want to eradicate religion [in India] you are cutting the vital lifeline” (Alice Boner, 1930).

Indian culture is rich and variegated, in which the ritual practice is not as strict and rigid as is typical occidental christendom. It possesses an organic form of sensuality where it titillates all the senses of the body: the fragrance of the incense, the prismatic colours, the gustation of the prassad, the melodious music, and the unique texture of the offerings. The ritual bring you back to the body, to the sensation, and awakens its subtle resonances. The sacred geometries activate the correspondence between the body, the cosmos and the divine. It teaches and investigates the essential knowledge of reality.

En Inde, vie mondaine et religion cohabitent sans hiérarchie et on ne connaît pas cette dichotomie occidentale. Pour l’hindou, religion et spiritualité sont difficilement dissociables et existent partout à chaque instant. Comme le dit l’une des premières exploratrices du début du 20ème siècle qui a grandement contribué à faire connaître la richesse de la culture de l’Inde: <<if you want to eradicate religion [in India] you are cutting the vital lifeline>> (Alice Boner, 1930).

La culture indienne est riche et colorée, dans laquelle le rituel n’est pas aussi strict et rigide que celui du christianisme occidental. Il possède une forme de sensualité organique, là où il stimule tous les sens du corps : l’encens pour l’odorat, les couleurs pour la vue, le prassad pour le goût, la musique pour l’ouïe et les offrandes pour le toucher. Le rituel ramène au corps, au senti, et vient en activer les résonances les plus subtiles. Géométries sacrées qui mettent en correspondance le corps, le cosmos et la divinité. Il enseigne et investigue la connaissance essentielle de la Réalité.

Special thanks to Ritam Banerjee for the photos he took while I was performing the puja on the Ganges’ Ghats. As for the re-reading and translation, my gratitude goes to Kweku for the English, my grandmother for the French and Ana Luiza Feres for her translation in Portuguese.

Remerciements particuliers à Ritam Banerjee pour les photos prises alors que j’accomplissais la cérémonie au Bord du Gange. Quant à la relecture et la traduction, toute ma gratitude s’en va vers Kweku pour l’anglais, ma grand-mère pour le français et Ana Luiza Feres pour sa traduction en portugais.

View Comments

No Comments (Hide)