The Philosophy of Low-Tech: A Conversation with Kris De Decker

I’m at a cottage with no road access, no connection to the electricity grid, no sewage system, and no running water. Instead, we have a small dinghy, an old solar panel installed in the 1990s, a compost toilet, and a small filter that pumps water from the lake. And it all works really, really well. But there are some drawbacks.

This morning, I was on the roof, holding two smartphones and an iPad, turning them in different directions to get some cell reception. I was starving for data. When those magical two bars appeared, I quickly tried to log in to Facebook—but it wouldn’t load.

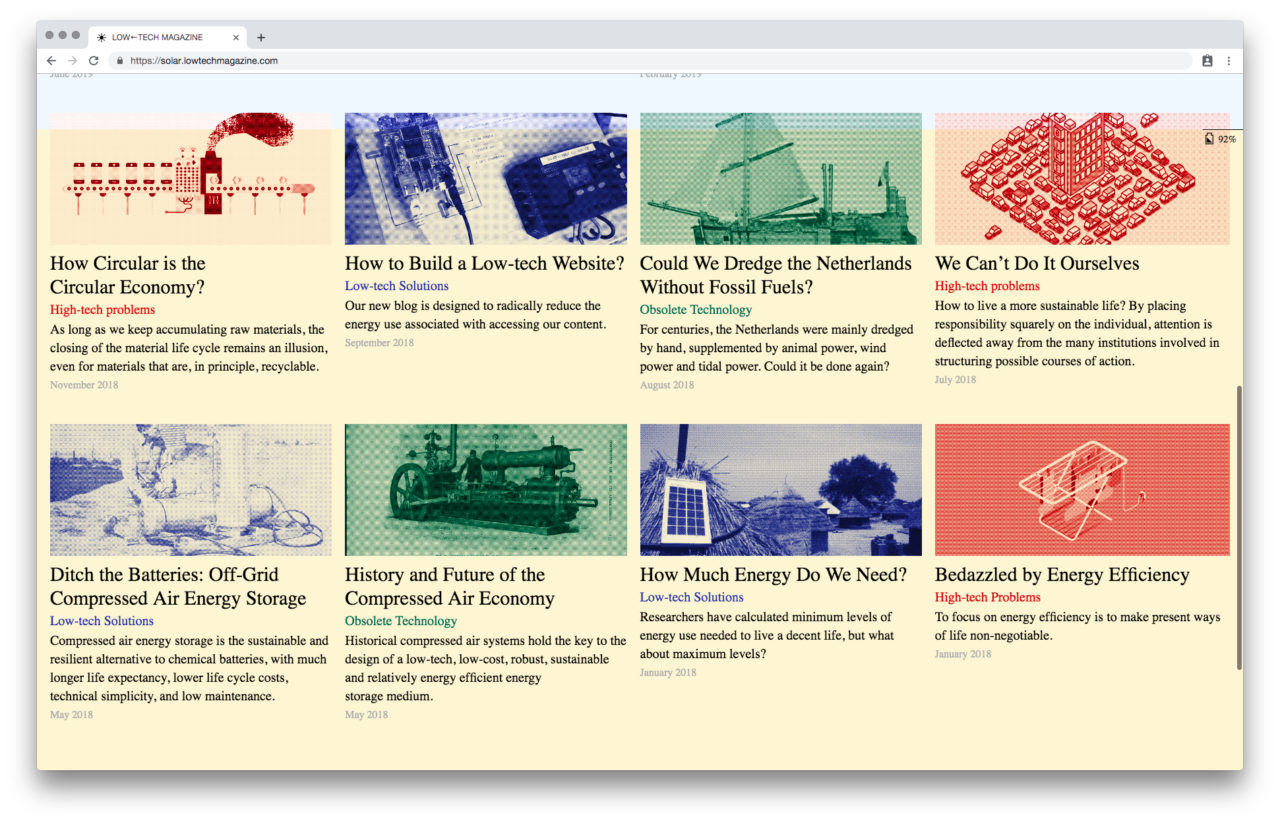

But I didn’t really need Facebook. I was trying to read an article from solar.lowtechmagazine.com. When I typed the URL in to my browser, it loaded almost immediately. Launched earlier this year, the site is 10 times smaller than your average WordPress site. And it runs on a solar panel in an apartment in Badalona, Spain.

Mr. Lowtech

Kris De Decker’s office is off-grid. Installed on his balcony are several solar panels, which power his laptop, as well as a model train set right next to his desk (more on the model train set later). He is the editor and primary author of Lowtech Magazine, which has been his bread and butter for almost 12 years now.

You can imagine some of the responses Kris gets. “I get this comment from readers sometimes: ‘yeah, but, you’re using the Internet—how ironic! Mr. Lowtech is using a high-tech Internet to tell the world to be critical about technological progress!’” But rather than ignore these kinds of snarky comments, Kris took them very seriously. “I always try to practice what I preach, mostly because it’s a very interesting research position. You have to live what you write about. So I decided to get my office off-grid.”

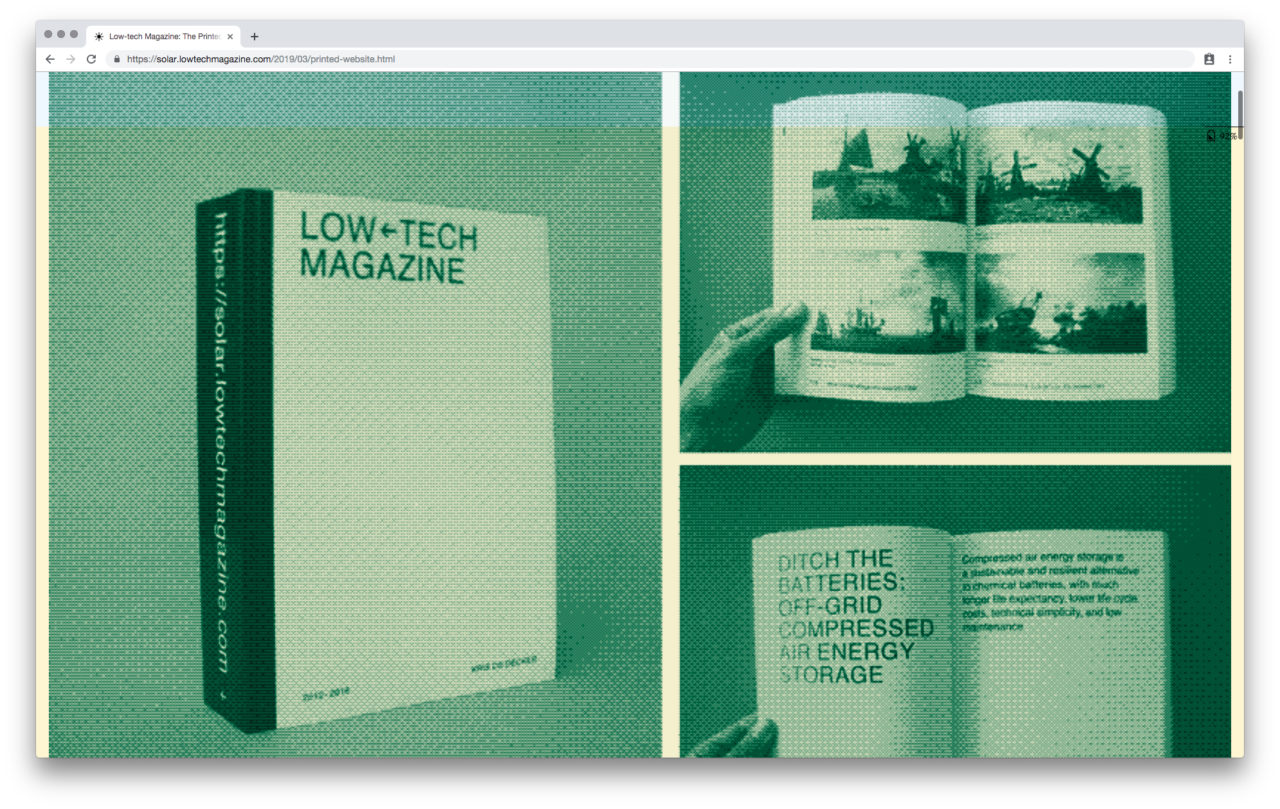

That knowledge led him to, eventually, build a solar-powered website with the help of Marie Otsuka, Lauren Traugott-Campbell, who were students at the Rhode Island School of Design, and Roel Roscam Abbing, an artist based in Amsterdam. The website is strikingly aesthetically pleasing. This is in great part due to the “dithered” images, a way to scale down images to 1-bit, greatly reducing the memory they take up, their upload time, and therefore their energy use. This image display tool was first developed for the first websites, but has since been largely forgotten.

It turns out that Kris’ low-tech philosophy, “if you want a solution for a problem, go look at the past”, also applied to building a solar-powered website. “I discovered that the same holds for the Internet. If you want to address the energy use problem of the Internet, which is becoming a really huge problem, you just look at the history of web design, and you see where it went wrong.”

But that wasn’t low-tech enough, apparently. Sure, Kris’ website can withstand a power failure or the world’s server farms shutting down. But what if the sun stops shining in Badalona, and his battery runs out? So Kris set to work to develop an even more low-tech website: a printed website—I mean—a book. “That’s really the most low-tech form of the website,” says Kris. “Of course, it’s only thanks to the Internet that I can actually sell it, and that people know me, but the reason why we go back to paper is because it still has its unique benefits: it doesn’t disappear if there’s no energy.” Today, as I write this article, I can see that the battery running the website’s server is at 15%. When it goes down, or when I no longer get service on my phone, I can just pick up the book, published this year, which I made sure to bring along to the cottage for when I couldn’t be bothered with climbing onto the roof.

What does “low-tech” actually mean?

But what is “low-tech”? Despite having thought about it for over a decade, Kris doesn’t have a clear answer. “I’m not a philosopher. I show things in very concrete examples, and I can only explain low-tech by means of examples.” So he gives me an example. “If you put my laptop and my typewriter next to each other, and ask, which is high-tech, and which is low-tech? Well, that’s obvious. But when you put the typewriter next to a quill pen, then it’s obviously a typewriter that’s high-tech. And if you think it through all the way back, well, then you’re writing in the sand. What is low-tech today is not low-tech tomorrow. It’s a completely relative concept.”

In a way, to talk about low-tech is more of a critical position. “Low-tech mainly questions the idea that ‘more tech is always better’.” Many proposed solutions are about adding more and more complexity. “Look at what we’re trying to do with cars,” says Kris. “The car is creating problems, so we make electric cars. We add layers and layers of complexity, by making it self-driving, putting even more infrastructure around it… that’s not going to solve the problem. It’s only going to make the problem worse. You introduce more complexities, you need to repair more afterwards.”

The dictatorship of the present

To get a better idea of what Kris means by low-tech, it’s best just to browse the website. Over the past twelve years, Kris has collected example after example of improbable technologies that people used centuries ago—which, if we used them now, could solve a lot of our problems. Spend some time going through Lowtech Magazine’s archives, and it gives a sense of overwhelming possibility—but without the aspartame-like sweetness of the high-tech promises from the Elon Musks of this world.

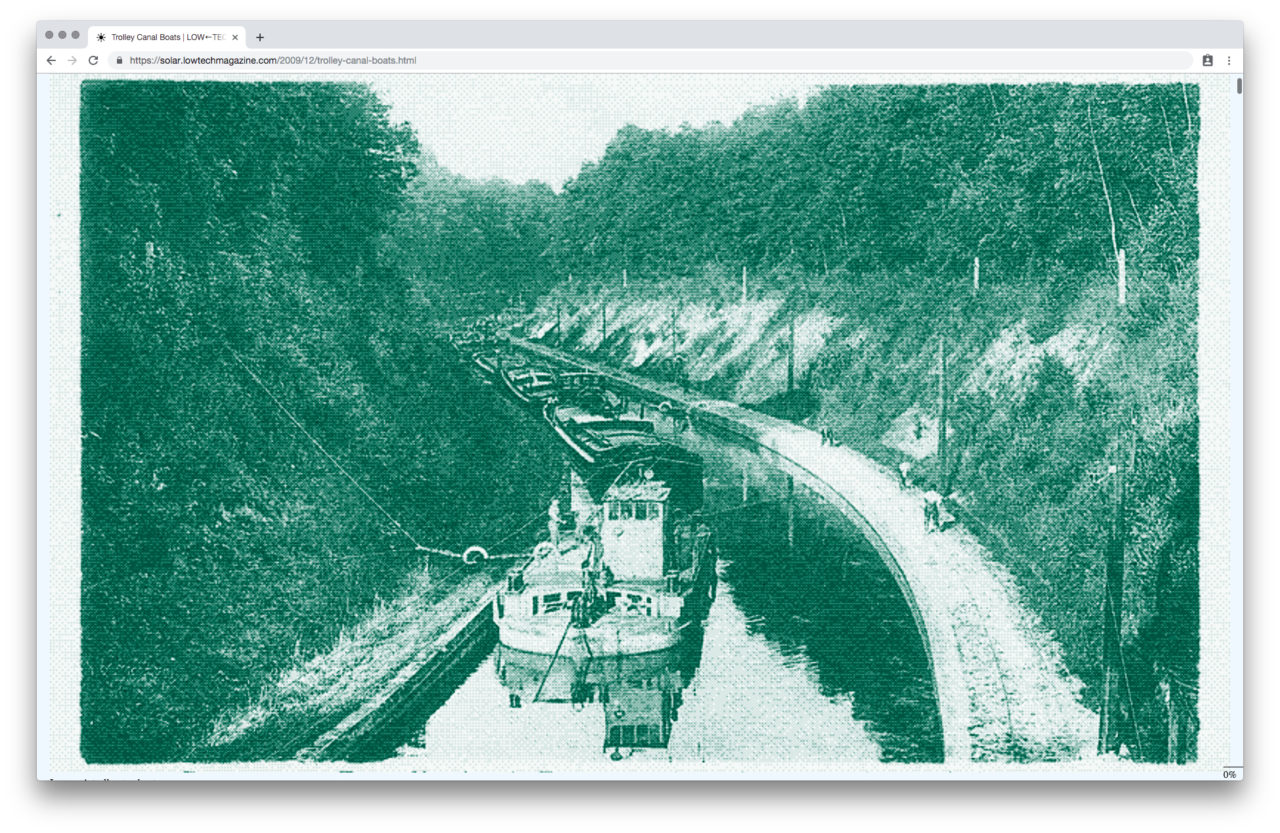

Kris directs me to the entry on trolley canal boats. Common in Western Europe in the early 19th century, often with many local variations, these were boats—freight or passenger—powered by electricity lines running above the canals, like streetcars today. “When I discovered them, I thought, no, this can’t be true, this is a joke. Everybody’s talking about electric cars these days. But these are much smarter and more sustainable, because you don’t need the battery.”

When presented with ideas like these, people will often respond that they’re not practical, they won’t scale up. But Kris points out that trolley bus systems used to be everywhere. The trolley canal boat alone ran for thousands of kilometers in its day. “People are convinced that diesel buses are better, because you don’t need the electricity lines. But, yeah, the problem is they basically fuck up the planet. If you think about it a bit more, a few power lines above your canal might be better.”

Building a different world

When Kris takes a break from work, he will often start tinkering with the model train set behind his desk. It’s not just any train set—it runs on solar panels, and it’s connected to a mini-steam-factory. “It only runs when the sun shines. But Adriana thinks it’s very ugly.”

The toy train set is not (just) a childhood hobby taken to an unhealthy adult obsession. It’s mainly a source of inspiration. When he first set it up, Kris realized he could determine the speed of the train by moving the solar panel into or out of the sun. “It was a very important insight because it means you can apply solar energy and wind energy completely without energy storage. If you adapt to the weather, if you accept the fact that the train only rides when the sun shines, everything keeps working anyway.”

Would people really accept it? Kris agrees that it would be very different from the world today, but remarks that we already do a lot of things depending on the weather. “If you’re a wind surfer, you go out when it’s windy. If you like to go to the beach, you go when it’s sunny. If it snows then you go skiing. We do very different things in winter than we do in the summer. Agriculture is totally based on the seasons.”

Kris points to the importance of having an understanding of history. Our ability to decouple ourselves from the weather—like building 25-story ski hills in the middle of the desert, as people have done in Dubai—is actually extremely recent, and short-lived. “We are in a very unusual situation that is very abnormal, where we can do everything that we want, where we have a temporary energy source that allows us to do anything we want, and whenever we want it. And if you get addicted to that, you’re in trouble. Because the hangover is going to be harder afterwards—and then going cold turkey isn’t going to be nice.”

Extremely online

I think about life at the cottage. I come here, not because I hate technology or because I want to escape society. Like many people I know, I find it necessary to sometimes limit myself. Friends regularly shut down their Facebook accounts, get rid of their phone, or spend time in the country, where life is more manageable. Many Silicon Valley CEOs don’t let their kids use social media—they know, more than anyone else, how addictive their websites are. One of the main reasons why Internet energy use keeps growing, says Kris, is because we are more often online. He wonders, “Why don’t we have websites that have closing hours, or like mine, that depends on the weather? Then you might say, ‘oh, well, it’s not that bad, I could come back later.’”

The solar-powered website, down to its very design, was built to illustrate the infrastructure that powers it. “We have this idea that it’s all in the clouds, that it’s not physical. But it’s just as physical as everything else. That’s why there’s a battery meter that’s in your face when you’re reading. The website wants to show you: this is how it actually works.”

A foot on the brake pedal

The present moment has a lot of momentum. “We know there’s a very sharp bend coming, but we’re not even braking, we’re accelerating,” says Kris, near the end of our conversation. “People think that accelerating is the way to jump over the bend and land on the other side of the mountain or something. Well, I guess you never know.”

But, if there’s anything that Kris has learned, it’s that history shows us that we usually don’t land in one piece. “If you invest in the stock market, they will tell you that ‘the performance of the past is not a guarantee for the future.’ It’s not because you buy stocks that went up, that they will keep going up. The same goes for technology. People also say, ‘we will find something else, we will find another source of energy.’ But there’s no guarantee that we will find it. And even if we find that new energy source, then we’re completely dead.”

Kris’ solar-powered website runs entirely on an electronic device smaller than a smartphone. But the ideas you can find in it are big. The train of civilization is going full-speed ahead. Maybe these ideas can inspire some people to apply a bit of pressure to the brake pedal.

When I finish writing this article, I will have to climb up to the roof again, to send it to my editor. But I don’t really mind.

Aaron Vansintjan writes about ecology, politics, and cities and lives in Montreal, Canada. He tweets at @a_vansi.

Thoughtful article but low-tech will be our ultimate doom when the sun will end up its fuel in 5 billion years.

Another thing is to aspire to higher and higher tech but only for important application instead of for silly things like skying in the desert. A particle collider for example would be a much better and useful idea.