Name Yourself

This essay is part of the monthly column by Collective Culture. Written by Bobbi Adair and edited by Jazmin Batey.

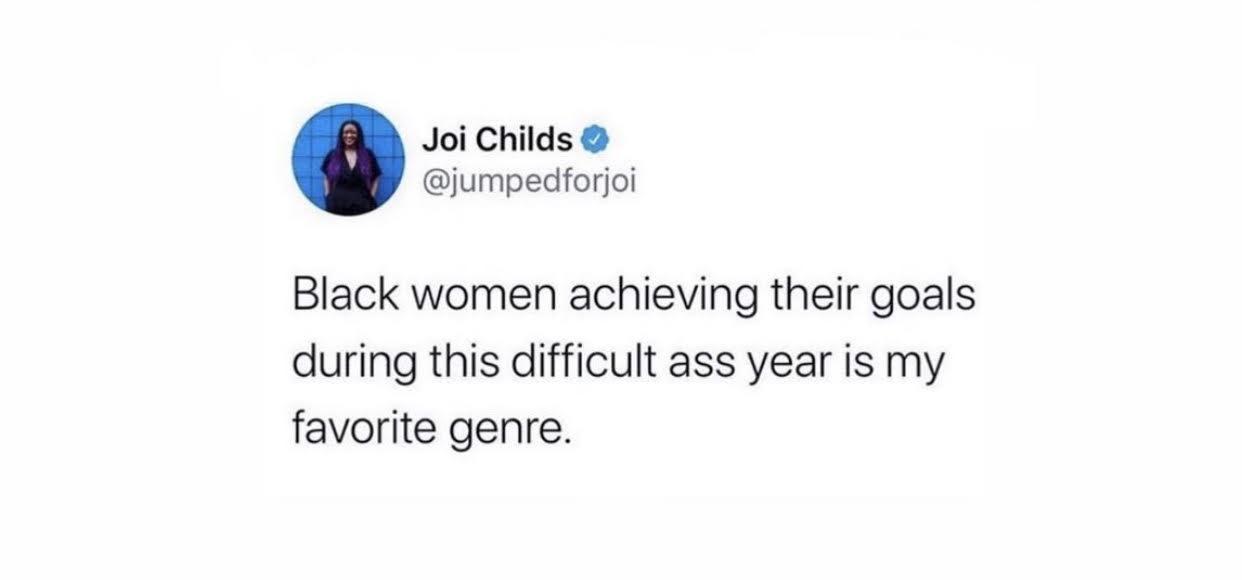

It’s been an(other) interesting year to be a Black womxn. There has been a tumultuousness that has clawed at our spirits, our minds and our bodies. But, it remains true that she who has experienced deep grief is capable of supreme happiness. So, before the new year approaches, here is yet another piece on the importance of representation. For me, representation is more than symbolic; it acts as a reminder, as reassurance and as a tool for reimagining who we believe we are and who we want to be.

This year especially, I’ve had to hold tight to the sources of inspiration that shaped my past, colour my present and inform how I envision the future. Like otherworldly signs, cultural cues seemed to appear, or reappear, into my line of sight right when I needed a laugh, a feeling of community and a renewed fervor to push through. Regardless of the idiosyncrasies that detail each fictional character I watched, there is an undeniable agency that supersedes any limitations created by space, by time or by script. Sociologist and hip-hop scholar, Tricia Rose once said,

“These images are opening up possibilities, revising what men and women think women ought to be, even if they wind up endorsing patriarchal norms in other ways. Hollywood has to reaffirm the status quo, of course, but trust me when I tell you that just by opening those gates, they’re creating a rupture they may not be able to suture.”

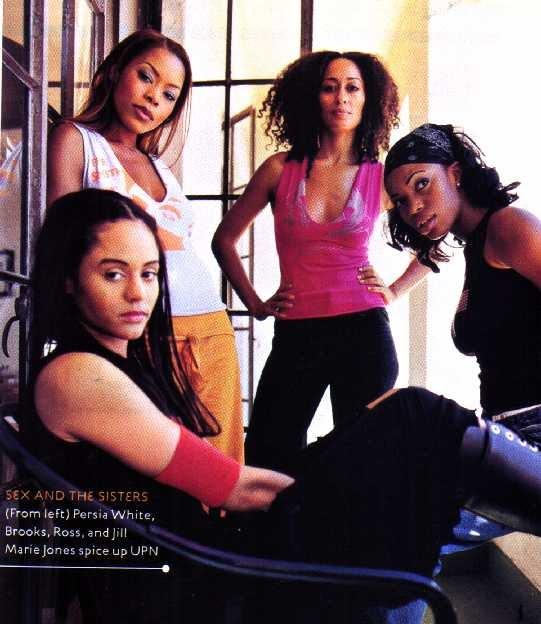

Recently, there have been many dynamic representations of Black womxn that have come to, or returned to, the forefront of influence: the syndication of Girlfriends, via Netflix, the spectacle of the US election – highlighting the power of Black womxn like Stacey Abrams and Kamala Harris – and the success of HBO’s Lovecraft Country. I have watched past, present and future versions of living and imagined Black womxn coalesce in a series of moments on screen that have given me cause to reflect. You see, “Black feminists have long insisted that we understand Black women as having multiple social identities, which coexist simultaneously; they are almost never reducible to a single one of those identities,” (Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor) and for every iteration of the Black womxn that I have absorbed and clung to, I am grateful. Black womxn have never truly fit the supporting roles or archetypes assigned to us; but seeing parts of myself and my realities reflected in them has been an anchor in a wide, white sea of homogeneity.

In Girlfriends season one, episode three, Joan states, “Toni, you are the bitch I’ve always wanted to be,” and that pretty much sums up how I first felt about each character in the show. Barely grown enough to understand some of its innuendos while it was on the air, Girlfriends was a formative influence on me, akin to the older sisters I never had; and, a look into what “kind” of womxn I might choose to be. Was I Toni: powerful in my sexual prowess, the embodiment of making conspicuous consumption look good? Was I Joan: sure of my morals and an avid overthinker… a testament to my own neuroses? Was I Maya: as loyal, hot headed and honest as I wanted my own voice to be? Was I Lynn: nah, I wasn’t Lynn… but her care-free spirituality, endless desire to learn and her need to be cared for by her friends personified a reliance on her girls that I could relate to.

While there were many Black, female archetypes I ingested as a pre-teen and teen, Girlfriends was the show that felt the most influential among the Black womxn I knew. Like a child eavesdropping on the Saturday kikis at the hair salon, the 8 years the show aired felt as short, and as long, as the 8 hours it took before my own wash and blowout or braidup was done. In the televised world and in that hair salon, time hardly seemed to exist. Between those 8-hour salon visits and the 8 years of Girlfriends, I took heed of the warnings and trade secrets. I inhaled their words on success, strife and sex like the Pink hairspray that I loved the smell of. I stored their lessons inside me until I could eventually relate or emulate my teachers. At some point over the show’s tenure, I realized that I did not have to choose which of the four womxn I wanted to be most like. Their growth was as alterable as my own. Watching them then and now, I have found myself in Joan, in Toni, in Maya and in Lynn – and eventually in none of them and all of them at once as I found my own stride. Even if the sporadic resurgence of support for Black womxn is a trend that is regularly exploited by pop culture streaming services like Netflix, for many Black womxn, the characters on this show, and its recent return, represents a validating reminder of our beauty, insecurities, traumas and heartaches, but most of all the importance of sisterhood and the vibrance of that love. As one of my own girlfriends recently said, “why would I have watched Sex in the City when I had Girlfriends?”

Yet, I can understand arguments touting that representation often equates to symbolism for symbolism’s sake; that “we need more than the tropes of Blackness and the imagined solidarity implicit within them” (Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor) to truly understand where we came from, where we are and where we will choose to go. I can especially understand this sentiment when we think of politics and the expectations that seem to accompany the Black vote and the Black leader. In Canada, Annamie Paul recently became the Green Party’s first Black leader, not to mention the first Black leader of any federal party. As was to be expected, national and international headlines, such as “Highly symbolic’: Canada’s Annamie Paul becomes first Black party leader” (The Guardian), could not help but place emphasis on her Blackness first and her political agenda second. Like Paul, the appointment of the U.S. Vice-President elect Kamala Harris – the first Black womxn to win the vice presidency – was also a tale of reductionism. For both Paul and Harris, the effectiveness of their political agendas have been highly criticized. Yet, the spectacularized moments in which they gained recognition, as “firsts” in their field, is a moment I cannot eschew or let pass uncelebrated. These womxn have still managed to rupture what was once sutured, as Tricia Rose said. For me, it’s when the T.V. is on mute and I look up and see a version of myself commanding space, time and the ears of millions. There is a flow of pride that waves through me knowing that Black womxn have rewritten history by writing themselves into a complex present; creating a future that has no choice but to acknowledge them beyond their symbolism.

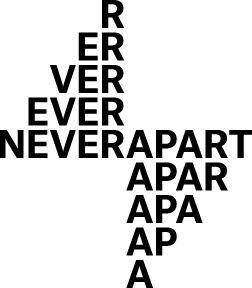

“Where do you want to be? Name it. Who do you want to be? Name it.”

Black Cyborg Goddess to Hippolyta, Lovecraft Country – “I Am”

In an interview with the mother of Afrofuturism, Octavia Butler, Tananarive Due describes Afrofuturism as “Black artists’ proclamation of ‘I am, I was and I WILL BE…Afrofuturism is the audacity to imagine a thriving future for Black people, or any future.” Drawing from the history of the African diaspora to imagine liberatory possibilities for the future, we are able to witness the otherworldly journey of discovering oneself and experience true freedom. Especially for Black womxn, who have been deprived of the energy and space to imagine themself to be whoever they choose, Afrofuturism depicts a reworking of time where womxn are empowered, know themselves outside the limits of patriarchy and can lead the saving of worlds. Lovecraft Country’s formidable matriarch, Hippolyta, propels us toward a vision of the boundless possibilities we can embody as she discovers infinite versions of herself as she travels through a multiverse of limitless earths. Choosing to name herself Hippolyta the warrior, the discoverer, the cabaret dancer, the wife and the mother, she realizes that the prison her identity once existed in was also the key to her freedom to define and redefine herself endlessly.

2020 used to sound like the future to me, one I could not accurately imagine myself in. Living through the chaos of this year felt reminiscent of the past lives of my ancestors. And somehow, still, Black womxn took each present moment proffered and found a way to unite further, lead more loudly and literally take up space to redefine our future. Regardless of past, present or future representations, Black womxn never ceased to remind me how they raised me, how their tenacity strengthens me daily and how their inability to be limited will always create meaningful differences in each life they influence. Just by knowing themselves and being themselves, even while fighting to discover themselves, they have led me to myself in ways as unimaginable as the years to come.

So, here is to another interesting year of being a Black womxn.

About the Author

Often referring to herself as a temperamental Taurus, Bobbi is twenty-something and tired on most days; currently occupying space as a Black woman in advertising and creative brand strategy in Toronto. Bobbi expresses her dreams, fears, experiences and most irksome musings about race, technology and popular culture as a member of the Collective Culture writing team. She also dabbles as a writing coordinator, making use of her teaching assistant experience and general love of weaving words.

If you’re looking for her, find her here: @_bobbidigital

View Comments

No Comments (Hide)