Testimony of a Black Woman in Montreal’s Creative Scene

Content warning: this story contains elaborates on details of misogynoir, a form of misogyny directed towards Black women where race and gender both play roles in bias. It addresses harassment in the workspace and suicidal thoughts. This text will require the reader to do some Google research because our job is not to provide definitions of theories that have been studied and experienced for over 400 years.

I have wanted to tell my story for years. Through my healing process, it has been challenging to gather the courage to write this.

The rare times I have shared this with friends IRL, my experiences were reduced to the result of the unavoidable reality faced by any “young creative” as the necessary steps anyone serious about their careers must take. I call these situations violent and misogynoir. For the last 10 years, I have suffered in a resounding silence in my hometown Montreal, the so-called sweet French-speaking Canadian cultural hub where I was born and raised. Growing up here, moving around using public transit from the age of 10 to go to school and dance classes shaped the city kid I am today. I have developed a very peculiar sense of attachment with Montreal: she is my weird mixed mom. I wanted to be involved in the multi-cultural aspect of the city and the beauty of it. Being Francophone, Canadian and Black is a specific experience.

Adding to this testimony, I want to share that both of my parents are activists and have kept working on social and political issues since the 80s in Quebec. They gave me a solid education about my history, my identity and the tools and ability to defend myself. I began to understand that I was a rare case of a Black person who had this sort of role-models at home. I was able to fully embrace this power and have been working as hard as I can to empower others working in the cultural field around me. Black people have been creating such an incredible wealth of culture coping with atrocities generations have been experiencing, yet, White people have constantly been capitalizing on it. For example, several music genres such as blues, jazz, hip-hop, techno and others were created by Black people as a testament to their reality and experience. This historical fact was erased under the name of capitalism. Not acknowledging it is both a privilege and ignorance.

Recently, I attended an event organized by a national media outlet with whom I had collaborated with a few weeks prior. Another guest, a journalist, said that I was a conspiracy-theorist for talking about systemic racism, followed by and the classic ‘’we’re not in the US’’. That type of people does not want to acknowledge systemic racism exists and is present in Quebec because they seem to think BIPOC want to recreate the similar racial dynamics, which is completely absurd. When in fact, we are only seeking political, economic, personal and social equality. The lack of empathy towards us opens the way for racism. If they cannot be empathetic, how could they understand that they need to work towards unlearning notions they have been taught for over 400 years?

The way up

After graduating from CEGEP, I had the chance to land a first job as a receptionist in one of the most prestigious recording studios in Canada. After a good start, my working conditions became humiliating, degrading and exhausting very quickly. After exactly a year working there, in September 2013, I got fired from my functions for what the studio manager labelled as “lacking motivation”. I was working longer hours than the imposed 9 to 5 schedule, always the first at the office around 7:30 am, cooking and serving food to clients sitting in the office, without eating nor taking breaks because ‘’ clients and staff needed the best service at the office’’. I was basically a waiter, a cook and a runner altogether for an honorary fee of 12$ an hour on a full-time schedule.

At the time, I would rarely see a Black woman working in the local creative business. So many of us with the classic protective saying from Black parents telling their children “to work harder than White people” because we never had the same privileges. It was already challenging for myself to accept that I was worthy to be seen and heard and yet I was ‘’lacking motivation”. I took this job because, at the time, I thought it was the only way to work my way up. Instead, every day was humiliating. I had to force-laugh at racist remarks from sound engineers, studio managers, company shareholders and their clients hailing from the finest and most hip ad agencies of the city. Some of these ad executives didn’t even look me in the eye when they needed a treat. ‘’Can I have my special coffee with 2 espresso shots and local bio almond milk ?’’, they’d ask. To make a parallel with what Robin DiAngelo, author of ‘’White Fragility’’ and sociologist states, some were vegetarians without ever questioning their behaviour and enforcing misogynoir. In fact, I wasn’t “lacking motivation” while catering to 4 studios with 6 people in a session, falling under the pressure of deadlines while serving fresh lattes on-demand on a daily basis. I just wasn’t enough.

Although I was qualified and had experience as an A&R and executive producer — I had released a mixtape, PIU PIU beat tape vol. 1 vol. (2012), vol. 2 (2012) and vol 3 (2013) and PIU PIU, a film about Montreal beat scene (2013) a self-produced documentary featuring some of the most talented and promising acts from Montreal — in their eyes, I had nothing good to offer. The ideas I suggested were never considered, or they were turned into jokes by the managers and stakeholders. For example, I had suggested that they collaborate on a project with a local producer that soon enough was raised to the status of a legend. And they ignored his work. In the eyes of the studio manager, I was only good to work as a servant in the sound recording studio. On a side note, he hated the record Voodoo by D’Angelo, which for me indicated that he had no soul. How could a sound engineer say something like that?

Casual racism is omnipresent in the workplace and other shared spaces, but some instances stung more others. One time, there was an overripe banana on a table. The studio manager with a coworker requested that I bake them a loaf of banana bread; yet another unappreciated extra-curricular task I took on. Another time, someone said to me referring to someone: “Is it the kind of dick you like to get? I didn’t think so, the boyfriend you live with is White, right ?’’ Today, I would know what to reply to such verbal aggression. Then, I had no idea how to go about filing a complaint against a sexist and racist statement. Now I can process and assess how violent this encounter was.

Six months in, there was nothing new aside from more frustrations and triggers. They hired a new employee, someone I was Facebook friends with, to help me with feeding ad executives, voice actors and clients. It only took two months for her to get promoted to production work. Now, she works as a director. She never studied cinema or previously worked in the field. The irony is seeing that same person minimizing my experiences of racism on social media while apologizing for her ignorance with heavy white guilt. The dynamic between Black women and White women in any work context is always frustrating because most white women abide by white feminism, which is defined by having racial prejudice towards women of colour and not acknowledging it in the holy name of ‘’feminism’’. Some of these dynamics between Black Women and a White Women in the workplace are often triggered by the patriarchy who wants the White oppressor to act their sole privilege and unleash competition between women. Even if many white Women working in creative fields are saying that sexism is “more present then racism”, I exist. Black Women exist, this shit exists. I still haven’t cried about it. I have yet to see a therapist to unpack it all but my rage keeps growing. So did my willingness to protect my Black & Brown siblings grew stronger as well.

Ultimately, it was a relief to get fired after such a stressful year. My self-esteem dipped the lowest during that period of my life. I even stopped working on personal projects. That is why there is no follow-up to the documentary I had released the previous year. Once it was over, I stood up and I could finally build something for myself. At the recording studio, I often had to choose between not being vocal and assimilating to white supremacy and hope that I would get promoted. Now, I have embraced the fact that I am a descendant of Dessalines, my ancestors fought the colonizers, my grandparents resisted the Duvalier dictatorship and that I was going to honour their legacy by speaking up my truth. Even if it meant being labelled “difficult”, “angry” or “unreliable”, I am willing to pay the price to honour the ones that came before me and demanded equality.

Truth hurts

They greeted me with arms wide open. It was a trick, I found out, and so was the precious work title I was given: A&R. It was an “opportunity to build my resume”, they said, while again, I was serving food, making coffee and completing other menial tasks in order to have a salary. I still did it for a while in order to pay rent and have internalized the capitalist notion of climbing professional and social ladders, but I felt conflicted. I was aware they were exploiting me holding an A&R and not getting paid accordingly, and I would provide valuable connections to their artists through my international network of music producers, and receiving no compensation or acknowledgement for my work. Challenging This exploitative structure earned me once more a label of being “unreliable”. This is the way many businesses operate and grow their value, without properly compensating and rewarding their workers.

While there was a structural issue with the way work and promotions functioned, there were also plenty of examples of overt racism, expressed openly and without showing remorse. We had been working on a new release, a song citing the N-Word in the title. Naturally, as the song was written and interpreted by a black person, it was their call to use it. My White coworkers immediately saw a free pass to say the repeat N-Word on several instances loud and giddy, citing the track. I tried to address the issue with them, but it was promptly brushed off and I was called ‘’ difficult & aggressive’’. On another instance, two recording artists, a singer and a rapper collaborated on a song together and a music video was filmed. The script portrayed them as an odd couple, enforcing the stereotypes attached to Black men as we see him depicting him as a criminal and being arrested for reasons unknown. It was the production’s attempt to market the singer to a “more urban” demographic and get the rapper his pop moment”. The singer addressed the problematic video 4 years after its original release. In that case and so many more, it took George Floyd’s death for many White creatives to wake up. Better late than never, I suppose.

A few weeks later, I quit my A&R position (which truly was a receptionist gig) because my pay was very late and my boss started to bully and pressure me once I mentioned my intention of pursuing my education. I no longer cared. That spring, Rhianna had just released ‘’Bitch Better Have my Money’’ I walked in the office shouting the lyrics of the song to make them understand that he needed to sign my last cheque. Given the office’s dynamics, I figured this was the only way my message would get across.

No rest

I still had the fire burning inside of me. But I was done with all the aggressions I was experiencing at work. I would let everyone know that I was no one to mess with. In 2016, I came back from my first European tour as a DJ and started working as a music curator for a local venue. It was a blessing to find myself in an environment that suited me. Several great opportunities came after.

Following that opportunity, I worked two part-time jobs, one in a record store and for an international media outlet. I was the first Black woman ever hired at the store, which is considered an establishment in Montreal. A coworker of mine, a woman, had already been struggling to make her place despite being one of the most brilliant selector and artist in town. The people I was working with were the kindest and made me welcomed, yet the difficult part was the dynamic between clients and myself. I was constantly asked where the hip-hop section was. Clients would see that I was available to help them prefer going great lengths to wait for a White guy — and ask him if their re-pressed limited edition of classic-rock record had arrived. I loved to prove them wrong with the music I played. The clients would love it, and I would delight myself with their surprised face when they were told that it was my selection.

The media company also did me in. They did not want me to publish where I was working on Linkedin. In their words, I was not even a real employee. They served me a legitimate explanation for it, although I had a job. I stumbled on company stats on diversity for the global company and noted that I counted for the 1% of Black Women working as a video host. It felt like I had to fight for my seat, for our voices to be heard while constantly having to justify myself at work. Again, I was not enough — even if I am behind a few series that you would probably watch. Every meeting I walked out upset at the way I was spoken to or by the fact that nobody t listened to any of my initiatives and ideas. Again, I was called “difficult” because my workload was overwhelming trying to managing an entire department and poor communication making it impossible. Working for them in one city to another, it just became worse. It has been an endless accumulation of labour responsibilities and pressure while management would casually indulge.

For this gig, we were putting our efforts at building a music festival in Montreal. The constant nepotism forced us to work with people with poor work ethics simply because of personal connections executives had. I had to collaborate with people who discredited my position as a music programmer. I had to work with venue owners who discredited my position as a music programmer. Those same people had many public complaints to their name for denying Black people in their establishments where they played hip-hop every night. When I addressed the issues with a manager about the matter, I was dismissed. I gave my heart, my soul, my time, my energy for a poorly paid job yet I couldn’t even find an allyship from the people in charge.

And, what now?

I turned 25. I started thinking about my 30s approaching. There was always pressure to build a better career. I was making a living as a DJ and when I mentioned it, people were in disbelief. I was told that I was ‘’too cute’’ to be one, I should have been a singer because of my looks. It felt reductive. The expectations are clear for a young Black woman, and being a DJ did not fit their preconceived notions.

In 2017, I burned out and ran away in reaction to the violence I took at work. I was still recovering from the incidents of previous years. The pressure others and I put on myself pushed me to a state where I was considering suicide. I felt that I was constantly reminded that I would never be enough, that no one would hear the social advancement I wished for Montreal’s cultural field. I was triggered by the sight of a familiar face or even the St-Laurent boulevard. I ultimately left the city to heal.

It is the first time that I share this story. Even my close friends didn’t know, only my mom did. With her help (she is a psychologist) I was able to understand and overcome this dark state of mind.

I have dedicated the past years to reading all books my parents told me about when I was younger and learning from other writers, scholars, activists to be as clever and informed as I could. Even if that would mean risking my career for exposing systemic racism and racial bias in the cultural workspace in Montreal. For the last 7 years, I have been travelling seeking information. I have witnessed affirmations from other BIPOC creative communities and I only wish to apply these revolutionary ideas. I moved to Brussels for 3 years. I came back because of racism. That racism prevented me from doing what I do for a living, DJing. I initially moved to Europe because to be the DJ I could not be in Montreal. A friend of mine, a Black Queer activist friend based in Amsterdam, talked me into going back home and start the work here, in a place where I knew who and what I have to deal with.

10 years ago, I didn’t possess the vocabulary to speak against the racial dynamics in cultural workspaces and recognize the dynamics of mysogynoir because most of the time, I was told by my employers that it was in my head.

Through all of this, I am trying to express how, working in the industry, I have suffered from microaggressions, casual and overt racism and systemic problems. I am still standing, still fighting for my Black & Brown siblings partly because the psychological damage caused by racism in the workplace makes it hard to move forward. It slows us on a personal, financial and psychological level by reinforcing the lie that we are not worthy, and at an institutional level, by refusing us credit and advancement where it is due. The system pushes for our skills to be ignored and our passion for culture remain unattainable and to be stuck doing a job we do not want to do. The field, just like others, has been capitalizing on Black culture.

As for my reputation of being a ‘’difficult’’, ‘’unreliable’’, ‘’angry and loud’’ Black Woman, well keep it coming. I am finally speaking my truth.

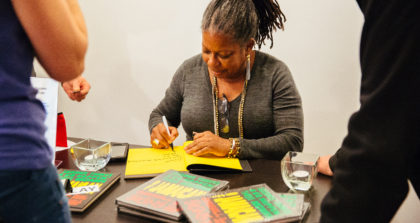

Follow Aïsha C. Vertus on Instagram, Twitter and SoundCloud.

Edited by Christelle Saint-Julien

Photo credit: Yanko Peyankov via Wiki Commons

View Comments

No Comments (Hide)